Dec. 10, 2014

An emerging audience-sphere in South Asia

The following is a conversation-in-writing by Fatima & Zahra Hussain, which draws upon their own practice, the creative practice in Pakistan and the viewer that is in the making.

Creative practice is at stake in Pakistan, especially at a time where there is much happening, and everyone seems to be hungry for information, and more information. From twitter to facebook, newspapers, protests and TV talk shows, everyone seems to be narrating the same event.

The art school graduates have a bright but a limited future and one can see most of them paving their future in more or less predictable directions. Therefore the art school is bound to train them to smoothly enter their professional lives. The predictable directions are a handful of chosen architectural firms and galleries. The local art world is limited to the ones who have in the previous years graduated from the same school and so forth. Local contemporary artworks are undoubtedly promising and are also seen in the international contemporary art scene where one usually encounters quite a few Pakistani names in most of the biennales and art fairs all around the world. However, what happens is that the art at home fails to create (as opposed to entertain) a local audience for itself other than the one of international contemporary art that already exists around it. At the same time, some major events or happenings have majorly dictated the emergence of creative practice in terms of academia and its practical relevance in Pakistan. In a sense, the Declaration of War against Terror in Afghanistan and the declaration of free media in Pakistan in the last decade have curated the socio-spatial landscapes of urban environments and the development of the creative faculties within these.

Paal Andreas Bøe: So how did you guys come to think of the project [info bomb[1]]?

Fatima & Zahra Hussain: We were doing quite a few projects since 2009 such as the Redo Pakistan which was newspaper based and Slice, in which we basically drew a line between London Liverpool Street Station and Lahore City Station on the map and then started working on both ends with 10 artists from each city. It became an interactive project that went up online as an alternative map of the two cities. Around the same time, we were also targeting the media because we felt it played quite an important role in Pakistan now. We printed tissue papers in a large quantity with questionnaires about the media being the new regime and distributed the tissue papers widely in café’s and coffee houses in Lahore and Islamabad. While doing this, and seeing how widely it was received, we realized the need to continue highlighting the role of the media even more.

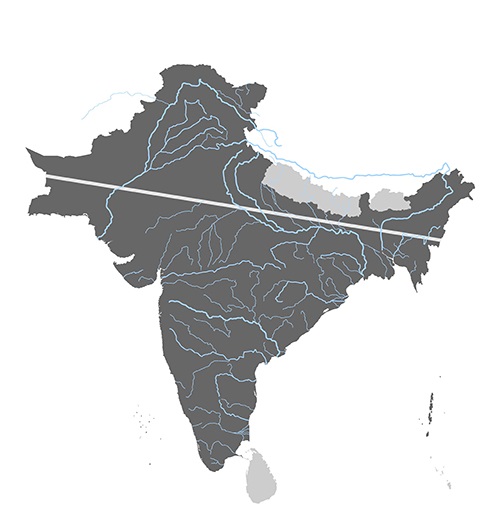

PB: I'm not sure if I understand the idea behind the line that stretches across the continent.

F&Z: The idea of the line came up when we were thinking about a model to visualize interdependency between the two countries. How we in Pakistan are dependant on India for water etc. And the line that we have drawn gives Pakistan access to the rivers and India, the sea link. So if we have to co-exist, then we really need to think about larger things than identity.

PB: I see.

F&Z: And even within the last few projects, we have been thinking about the Radcliffe line and what does it do? Why is it this important and why is it so heavily guarded? Someone came along and drew the line for us and we are literally just following it!

So then we came up with a new UN Security Council document (fictive) that was made in 1947 (right before partition), stating that the borders will be drawn again in 2014. We ruthlessly slashed the subcontinent across and drew a new line. We got a lot of response from people across the country, from India and from Bangladesh saying “How can the line (border) be this straight?”

It is literally a comment on how ridiculous the line is anyway.

Z: But you see the important aspect of this art project is that instead of the two-nation theory, the geography this time is to be divided according to the idea of sharing natural resources within the region. They say, as the years go by, we are moving towards a scarcity of natural resources and perhaps this is what the future wars will be based on. Therefore, it seemed pertinent to us to suggest a strategy that addresses the sharing of these resources instead of drawing lines on land randomly.

F&Z: We got a whole mixed lot of response. Some people were really emotional, some got excited, some weren’t happy at all.

PB: But if we go back a bit, how did you come up with the idea of reconsidering partition? What brought you to that question?

F&Z: The projects that we were doing earlier were constantly questioning the borders, the lines, the division and how one could think of solutions with something so stark there, and every time the conversation would end in imagining the subcontinent without the line.

The line just had to go!

With all of these conversations, we think our underlying aim was to get the creative faculty in Pakistan to respond to these real issues, issues people relate to, and to get them to question the role that they are playing. We wanted to re-think our practice through our projects, through our mediums, communication strategies etc. And since both of us were teaching as well, we questioned the scope of that and were constantly re-defining what role the art school could play in all of this.

It is always hard for us to pin the project down somewhere, there are always various strands and they need to be talked about separately while being seen together at the same time. With this project we aimed at using/deconstructing the media to be able to question what it could do, while also dealing with a controversial issue such as the partition and to be able to do it for a diaspora that is somewhat disconnected from the current debates within the subcontinent.

P.B.: Z, when you worked upon a fairly large archive of transformation information in the South, you coined the term halocaust to explain the situation we were trying to find a solution to?

Z: Indeed, and this is how I define the word “Halocaust":[2] The ring comprising the various agencies that form around a disastrous event. From Halo and Caust.

Halo (n): from Gk. halos “i) Disk of the sun or moon, ring of light around the sun or moon. ii) The aura around a glorified person or thing.

Caust: Caust-ic (n) (physics) formed by the intersection of reflected or refracted parallel rays from a curved surface.

Halocaust is a concept developed through rigorous research by analysing contemporary geographical space as it has evolved in the last decade in Pakistan. Since 2001, Pakistan has been a key ally to the US in the War on terror declared in Afghanistan. This involved a complex network of strategies, relations, operations, responsibilities and pacts between these countries. Although the war is active in Afghanistan and the North-Western space of Pakistan, the effect of war encompasses a much larger area irrespective of territorial boundaries. The halocaust concept lies in the domain of geopolitics as it affects contemporary urban space and triggers a process of accelerated transformations. While we explore the present urban condition in Pakistan by examining the political and cultural ramifications of social and institutional networks present in different cities, we also engage with the situation at various scales in the relationship between power and space, and in the regimes of authority performed through spatial arrangements or assemblages. I would say, Halocaust is a censor to trace transformations, like a process that begins at the moment of a spontaneous destructive event, be it a natural disaster or a man made crises, followed by the convergence of various agencies to contain the chaos, which in turn ensure regulatory practices in space. This concept takes deeper interest in these relations by analyzing the spatial configuration of their operation, materials that are plugged into the architecture, the reshaping of urban space and the emergence of a collective subjectivity in a conflict-stricken society. It questions the active making of urban morphology; the role of the architect and the urban designers, the surveillance and security mechanisms and the incalculable effect of warfare as it seeps into the spaces of daily life. Through the intense archival procedure, the research material acts as the nomadic discursive element that becomes the point of convergence. It activates a forum around itself that dissects the site under analysis, something like what the media propagates.

F: And similarly, in my solitary practice I was interested in locating this surge of media and the network of audience that it creates around itself, and became aware of how often our work was mimicking/ staging/ using the strategies that media uses to communicate a set body of knowledge across. And within the last decade, media has been able to do what art in the subcontinent has been aiming at ever since the influence of the ustaad[3] started to diminish. By dismantling the screen of the television, one can understand the passive consumer’s ever growing interest. The television does not only demand a passive viewer but also a participatory one. The participation requires the viewer to construct the event that is being produced in various sections of the screen (the ticker tape at the bottom, headline in the left box, video footage in the right box, news-reporter fluctuating in between, the channel logo rotating in the top right corner etc.) The arresting nature of the device demands urgent inquiries for the creative’ in ways distinct to those of the recent past.

P.B: Perhaps you mean to say something indirectly about contemporary art systems by making this thoughtful analysis of a TV screen?

F: In fact, one can see the complete opposite in the networks contemporary art creates for itself. The implied viewer is not only passive but is also devoid of the sort of mode of seeing that creates a thinking viewer. Art happens in the production of knowledge, as goes the fashionable phrase, and bears a strong relation with knowledge because thinking takes place in art. A sort of thinking that is different from arguments and discourse produced. It is locked within the relationship of the spectator and the active object in the event of the visual field and inquires the modes of vision so as to reconstruct the composition.

The interest within my practice and research is to pave groundwork for performative strategies at the intersections between the city and the art academy. The focus of our collaborative practice is first and foremost these intersections that activate an event and occupy the public in order to allow for a more meaningful discourse.. They are the medium and the motor of production of a body of responses to a particular situation. The shifting of our roles from an artist to someone as a hawker, newsmaker etc. does not remain the only and main aim as such; rather it is about how the artistic production is conceived and projected and how it builds an active audience around itself. We are also not only concerned with the artistic production as such, what interests us more is the ‘mode of seeing’ it stimulates. How does a particular body of work create (as opposed to gather) the viewers around itself? How do those viewers negotiate their interpretation, if at all? How does this practice of negotiation inform the art production and aesthetics?

Z: I believe, the space for exploring the creative methodologies for responding to our environment can be seen directly in these territories that you talk about. That is why I came up with the idea of “Academy for democracy”, to clarify how we all contribute to the making of a particular space. This is where the creative practitioner and the technical /humanitarian fields of work intersect. The project LVS[4] centres upon the crisis as that moment which triggers transformation, for a new structure to become, a space to be reclaimed and re imagined. But what of the audience that gathers around this spectacle, this crisis?

Fatima Hussain is co-founder and director of Other Asias: Transnational Artist Collective (based in London, Lahore and Dhaka). She holds an MA in Fine Arts from Central Saint Martins, College of Art and Design, London.

Zahra Hussain is Director of the Laajverd Visiting School, Academy for Democracy, GB/ Pakistan, and Project Director of Bacha Bulletins, Laajverd & Common Wealth Foundation. She holds an MA in Research Architecture/ Visual Cultures from Goldsmiths University of London.

[1] The project used Paul Virilio’s concept of the Information Bomb to show how ideas, bodies, and networks assemble around a fictive UN Security Council document that demands the borders to be redrawn between India and Pakistan in the year 2014. www.thesubcontinent.com

[2] Stevenson and Lindberg (eds.), New Oxford American Dictionary (3 ed.), Oxford University Press 2010

[3] Mentor in creative practice. The word ‘ustaad’ is used to refer to the person who teaches.

[4] LVS, Laajverd Visiting School is an annual initiative to bring the creative, social science and development faculty onto one platform to respond to crises together. http://laajverd.org