July 1, 2011

The Performative Archive

Fluxus East and The Creative Act

Henie Onstad Art Center, Høvikodden

By Paal Andreas Bøe

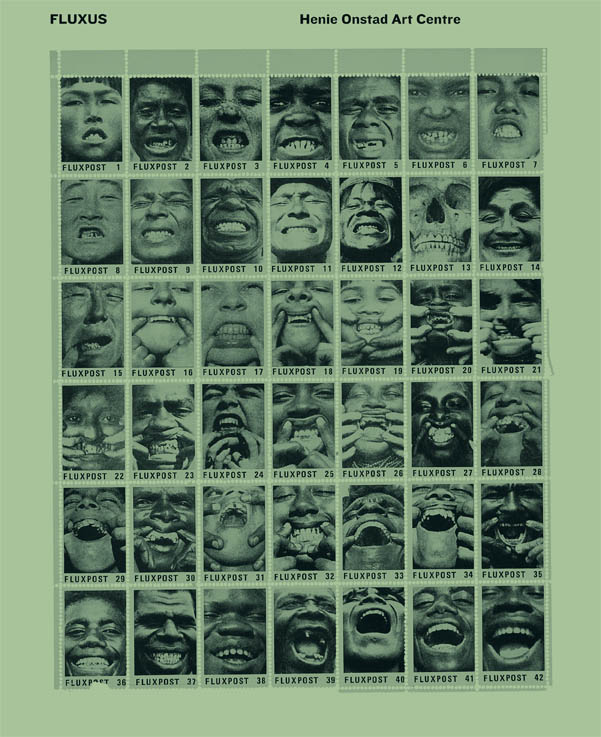

In Henie Onstad Art center of Høvikodden you would recently find archives erupting from their cellars, thereby reasserting the center's long tradition as a transitory arena for groundbreaking art: Specifically a re-archiving of the institution's long accumulated collection of Fluxus art.

An interplay of archives: Fluxus East and The Creative Act

For one thing, this comprehensive anthological procedure is puzzling because it consists of a tremendous quantity of artworks whos e very essence is to ironise over any synthesizing and conceptualizing attempt. Certainly, the exhibition (which a carefully designed catalog illustrates in its entirety) bears testimony to the historical intricacies and remarkable proliferation of the movement's 'negative', in-flux imagination since its early days, characterized by a merciless disruption of the institutional as well as the perceptual paradigms of Western art. It also works as a fine album for all the hilarious, seriously unserious 'event' posters and 'announcements' through which Fluxus communicated itself to the public, thereby ironically consolidating a coherent idea of its own anti-mythology. With a benevolent eye, it is even possible to see the act of archiving Fluxus as yet a repetition of this treacherous idea of a coherent aesthetics – in other words as a Fluxus event and performance in itself.

e very essence is to ironise over any synthesizing and conceptualizing attempt. Certainly, the exhibition (which a carefully designed catalog illustrates in its entirety) bears testimony to the historical intricacies and remarkable proliferation of the movement's 'negative', in-flux imagination since its early days, characterized by a merciless disruption of the institutional as well as the perceptual paradigms of Western art. It also works as a fine album for all the hilarious, seriously unserious 'event' posters and 'announcements' through which Fluxus communicated itself to the public, thereby ironically consolidating a coherent idea of its own anti-mythology. With a benevolent eye, it is even possible to see the act of archiving Fluxus as yet a repetition of this treacherous idea of a coherent aesthetics – in other words as a Fluxus event and performance in itself.

Still, the question one unconditionally asks oneself at Høvikodden on one of those particularly frozen and dark Norwegian winter nights of 2011, is whether these artistic strategies still have any momentum, flexibility and actuality left, not to mention in a local context. If the point is in the asking, it can definitely be said that Henie Onstad much more fruitfully questions the potential of the contemporary art institution itself as a political and historical space, than Fluxus aesthetics as such.

In a different sense in another part of the building, The Creative Act also investigates the idea of the archive – a rather heavily inflated artistic term after its surging popularity in recent years – and simultaneously reclaims the art gallery as an experimental ground for memory work and political action. Interestingly, the reflexivity of the two exhibitions largely stems from their juxtaposition and turns our attention towards the performativity of art.

Maryam Jafri: The semiotics of postcolonialism

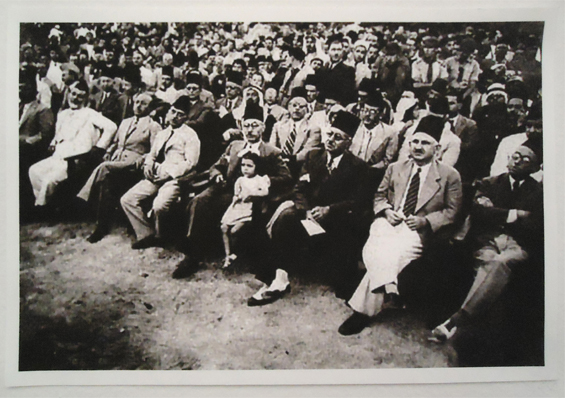

One of the participating artists in The Creative Act, Maryam Jafri, works with historical narratives and documentary to investigate the concept of the postcolonial. In the work Independence Day 1936-1967 she juxtaposes photo-documents of transition moments in former Asian and African colonies. The structure with which these pictures are mounted approaches yet refuses to form a pattern, somewhat resembling a sequence of letters, giving associations to both a kind of private language and to an act of 'archiving' whose rules are more or less indecipherable. All the more clearly, the gallery context and the idea of archiving reveal each other's lack of innocence as modes of historical representation – conditioned, as they always are, by rules which are not immediately visible.

While the last point is not very original in itself, this play with the background rules of interpretation can more interestingly be seen as a metaphor for what happens in the ceremonies themselves. Similar to the hidden logic of the gallery archive, the ceremonies are revealed as based on a hidden, common aesthetic language-game as staged performances; an implicit semiotics by which their processions, gests, postures, speeches, handshakes etc. become interpretable as public signs of transition to freedom. Paradoxically, this postcolonial semiotics only becomes visible because the exhibition context aesthetically 're-stages' and thereby alienates the meaning of direct participation in these public acts. Evidently this also demonstrates the contemporary conditions of the act of historical memory, and appeals to a repeated work of historical reconstruction. Just as much, the past ceremonies are reflected as fragile monuments in need of repetition for their political significance to be upheld in their respective countries and epochs.

This contemporary act of theatralization and alienation opens up a common dimension in these moments which often eludes the writing of history: The process of producing semiotic conditions under which future history can be written. The product of the work, therefore, is not to reflect the local meanings of historic transition processes, but rather to create a new scope for an archeology of the concept of the postcolonial itself. Jafri's images also effectively problematises this historical concept as a product of images; as the powerful fiction of a past stage in history in an era when the problems with which many of these countries struggle are just so clearly not – postcolonial.

In a more general sense which she shares with the other artists in the exhibition, one could say that Jafri's work reclaims the gallery as a performative space. The Creative Act is an exhibition which, surely enough as the catalog states in connection with Jafri, 'stages' the concept of the archive in an abstract, Foucaultian sense: as the linguistic system which preconditions any ordering and transformation of information, images and symbols.

This perspective would perhaps have been more precise if supplied with theories about performativity (e.g. Jacques Derrida or Judith Butler): Clearly, the recapitulation of historical material multifariously presented here is not only an archeology of conditions of the 'archive' of postcolonialism, but also an act of giving new life to old forms, thus transforming and performing them anew, but not the least filling them with yet new meanings, producing a contemporary, and evidently unfinished, normativity. In this ability to transform and reenact seems to lie the real political potential, not of Jafri's work alone, but of the entire exhibition.

Carlos Motta: Staging the theatricality of politics

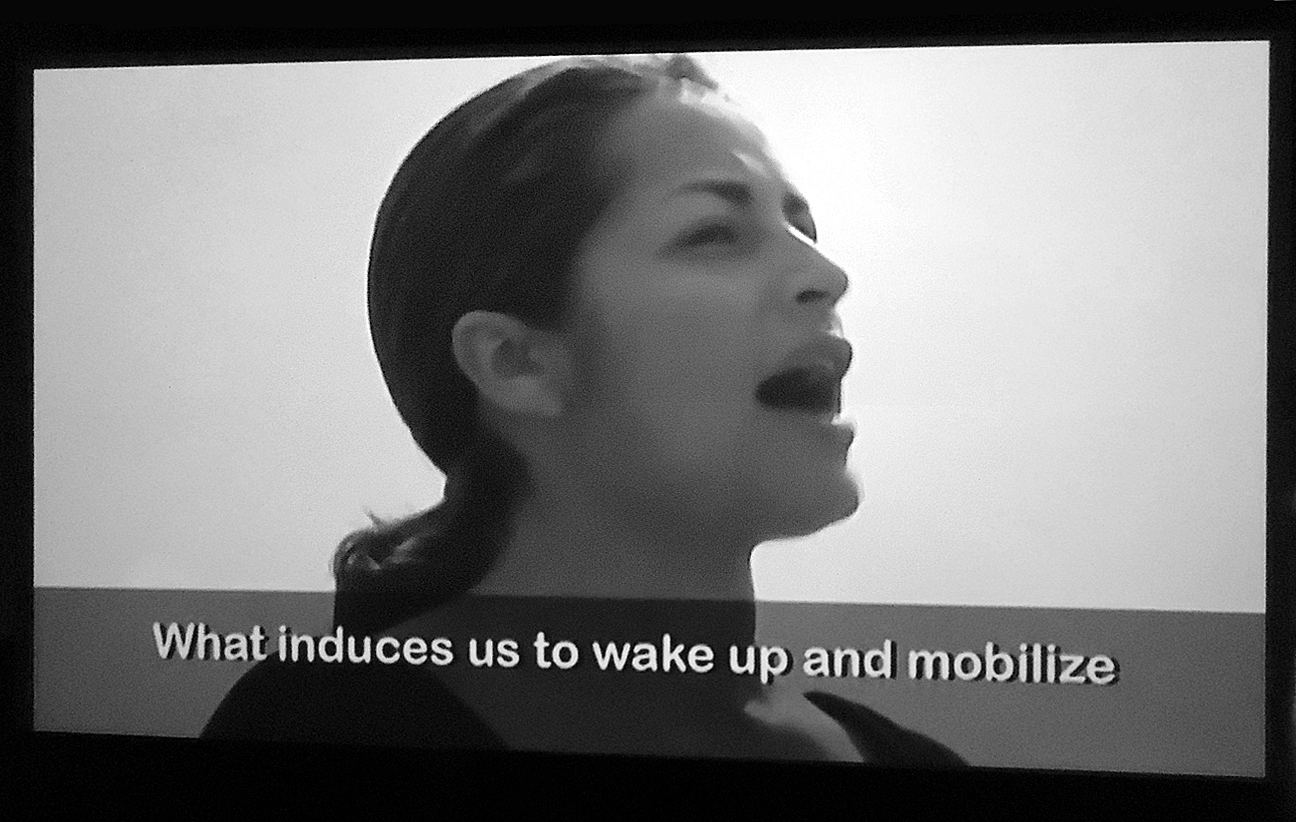

A strikingly contemporaneous example is a work by Carlos Motta, Six Acts: An experiment in narrative justice (2010). The work consists in the restaging of six political speeches from different epochs, originally performed by Colombian political opposition leaders/ presidential candidates who were later assassinated: Rafael Uribe Uribe, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, Jaime Pardo Leal, Carlos Pizarro, Luis Carlos Galán and Bernardo Jaramillo Ossa. Before they were taken into the art gallery context, these speeches were read aloud in public spaces (i.e. in front of the presidential palace) by well-known Colombian actors during the last presidential campaigns. Hence they became simultaneous demonstrations of the brutal exercise of censorship throughout Colombian political history, and of the lack of perspectives similar to those narrated, in the current political situation.

The actors re-read instead of reenacting or impersonating the speaches, stripping them to a large extent of artefacts, physical exaggerations and illusions usually pertaining to spectacle and performance. In an interview with Gabriela Rangel, Carlos Motta explains that his work is not meant to be a performance, but a form of political verfremdungs-based theater still producing affect and preserving a poetic side, yet resisting any mode of entertainment. The point would be to amplify the contemporary relevance of ideas. Motta says he wishes to create aesthetic experience in a political act to induce memory work, and thereby stimulate the reconstitution of a different 'collective subjectivity', in this era when '...the normative social, political and judicial models (...) have failed to repair the damage incurred not only by violence itself but also by the repressive dominant discourse on violence'.

One could further describe Motta's work as a subtle interplay between realism and anti-realism, as well as between documentary and fiction. Perceived from one side, the speeches employ a documentaristic rhetoric of neutrality by 'merely repeating' meaning, and by pretending to abstract from (both past and contemporary) context and the personalities of the performers.

On the other side, in its interplay with the surrounding political discourse this quasi-neutrality immediately transforms into a fictional, theatrical rhetoric: this theatralization produces affect, due to the contemporary invisibility of the kind of discourse on peace and civil rights to which these historic speeches belong. Combined with the memory of the former speakers' execution it effectively becomes a political act, pointing to a manifold hypocrisy of the current discourse on violence: '... an eerie dislocation of time and place occurred when hearing Jorge Eliécer Gaitán's speech from 1948 where he poignantly demands President Mariano Ospina Pérez to stop violence and reminds him that 'our flag is mourning'. Gaitán's words re-spoken today in front of the presidential palace were strikingly contemporary; they spoke directly to Uribe's power' explains Motta.

A crucial point here is off course also what happens when Motta's work becomes part of an exhibition. It is obviously impossible to claim that the recontextualisations of the speeches into the gallery is a political act in any way remotely similar to the contemporary act of performing them on-site in the Colombian context. However it more easily merges with the already active idea of the exhibition room as 'archive' that we have encountered in Jafri's work.

Similar to Jafri's focus on the concept of the postcolonial, Motta's becomes more of a general contemplation on the 'theatricality of politics' – a reminder of how the mise-en-scène and public enactment of political agendas almost unavoidably turns into totalizing world view paradigms which tacitly limit our scopes of perception and action, and need to be challenged.

Nevertheless, what strikes this spectator all the more forcefully, is that the exhibition room, virtually like an echo, constitutes a disturbing condition that is both abstract distance and immediate experience at the same time, triggered by the rereading of the speeches in the Colombian setting. In that sense, the room more or less forces us to understand the possibility and necessity of acknowledging and readjusting our political perception. The Colombian 'experiment in narrative justice', therefore, is not only an aesthetic and political act provoking affect over stretches of time, space and thought, but also literally a local case of global inspiration for a common battle of justice. Motta ambiguously situates his videos in between the walls of the white cube, as a simultaneously crucial and superfluous framing; a performative concept of the archive.

Towards a performativity of politics of art?

Confronted with this concept and The Creative Act as a whole, it is clearly not only the institutional preconditions, but also the possibility of upholding the critical potential of Fluxus aesthetics over time which seems to be at stake in the neighboring space at Henie Onstad. One could hence be tempted to turn Adorno's predicament for modernist art against Fluxus, by asking if not also such an uncompromisingly anti-art/ anti-modernist movement might be doomed to stagnate in, and contradict, its own founding principle sooner or later (although the exhibition catalog insists on its contemporary relevance). Anyway, in a deeper sense, what seems to motivate the different approaches to the archive at Henie Onstad, is the search for a general rule by which art can maintain its political agency over time. Their continuous redirection of our focus toward the performative, norm-generating side of the creative act (as well as the art institution), toward its implicit 'archive' of conditions of expression, seems to provide an elusive, transitory answer to the question.