December 28, 2013

A focus once in a while on plans and projects that are at times not known:

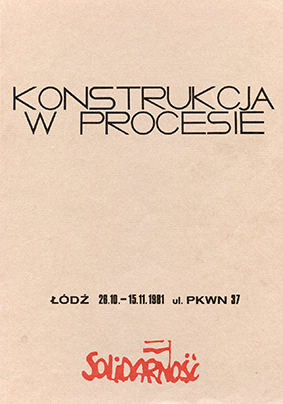

Robert Filliou’s Art-of-Peace Biennial (Hamburg, 1985) and Ryszard Waśko’s Construction in

Process (Lodz, 1981)

By Federica Martini

1. Appeals for alternatives: Art-of-Peace Biennial, Hamburg 1985

“On the same basis as Kassel, why couldn’t there be a show, like a biennale or a triennale, of works by artists that deals with the specific problem of making the world a world with peace and harmony… It might be very interesting as a kind of focus once in a while on plans and projects that are at times not known. … Perhaps little by little it could become like a meeting place where every two years, for instance, people would meet. You can imagine what a different catalogue it would make than the one of Kassel documenta…”

Robert Filliou in conversation with Joseph Beuys (Wijers 1996, 260)

As early as 1981, artist and previous UN-officer Robert Filliou started imagining The Art-of-Peace (A-o-P) Biennial, around the same time when the first edition of Ryszard Waśko’s Construction in Process (CiP) was taking place in Lodz, Poland. Based on gifts as well as on performative and discursive situations, both A-o-P and CiP developed in a collectivistic spirit, with manifest goal of offering alternatives to contemporary biennials’ adjustments to the art market and current geopolitical assets.

This critical line first emerged around the 1968 Venice Biennale, favoured by Italian students’ protests that condemned the institutional contradictions of the cultural establishment. Prepared by strikes and statements, the protest against the Venice exhibition acquired a symbolic status during the openings, because of their international visibility. Protesters targeted especially the Biennale award system and the Sales Office, accusing the exhibition of being “dead”, “fascist” and a clear expression of the “cultura dei padroni” (culture of the owners). The increasing strength of the strikes and of police repression prompted several artists taking part in the 1968 Biennale to react with solidarity gestures and clear stands on the mingling between art and market. On the occasion of the opening in June 1968, some artists decided to boycott the official events, close their venues or turn their paintings towards the walls.

Among the cultural scene, comments on the protests also included one maverick voice, that of artist Pino Pascali, author of the manifesto “Io la contestazione la vedo così” (How I see the protests) (Pascali, 1968). In his text, Pascali agreed with the protesters on the limits of the Venice Biennale, but strongly advocated for an alternative coming from inside the art world, in order to avoid risks of manipulation on the political side.

Though little known outside Italy, Pascali’s text was in the mood of the times, and would resonate in several artists’ statements dwelling on the social and political role of the artist including, one decade later, Joseph Beuys’ “Appeal for an Alternative” (1978). Beuys’ Appeal introduced many of the themes at play in his intervention for the 1982 Kassel documenta VII, including the experience with the Free International University that Beuys co-founded in Düsseldorf in 1973. Meant as the enactment of a “spiritualized economy”, the project consisted in planting 7000 oaks in Kassel and was funded through Tsarenkrown, an action where the sale of a melted gold crown transformed into a hare implied the passage from traditional power symbolism – the crown – to an image of peace – the animal (Thompson, 2011).

In the background of Beuys’ proposal for Kassel was also his recent meeting with the Dalai Lama. That encounter and the documenta experience, widely discussed with Robert Filliou in 1982, eventually provided the ground for the first conceptualisation of the A-o-P Biennial. It was then that Filliou introduced the idea of the A-o-P, an event seeking to subvert the political angle of international shows. Providing a platform for different geographies of creation, the A-o-P Biennial was to be an itinerant and regular meeting for a transnational community based on spirit, where artists and scientists could establish a dialogue. At the basis of the event was the assumption that the spiritual emergency caused by the capitalist model could not be dealt with by way of politics, as Beuys stated, but should have been addressed through an artistic perspective (Wijers 1996). And in order to produce an effective artistic response, art needed to radically rethink its logics and rely on international cooperation and solidarity, rather than on national competition.

Filliou sent out the invitation for A-o-P in November 1985, just one month before the first edition opened its doors in Hamburg. In the call for contribution, the event is profiled as a “periodical gathering of artists presenting their individual contributions to [a] collective (re)search”, where the main thing at stake may be “a matter of art getting back its intuitive thrust” (Filliou, 1985).

2. Solidarity and gifts: Construction in Process, Lodz 1981.

The intuitive momentum was central to A-o-P, where artworks and artists were meant to be present at the same time, in order to produce, and not only display, cultural exchange. A similar attitude emerged in the early 1980s in artist Ryszard Waśko’s CiP. Returning back from the group show Pier + Ocean: Construction in the Art of the Seventies at the Hayward Gallery in London, Waśko started imagining an event that would present international contemporary arts to a Polish audience in Communist times.

Going back to his participation in Pier + Ocean, Waśko recalls his admiration for the works by artists such as Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, Richard Nonas and Sol LeWitt that he had seen in the show (Lyon, Wei, 2005). Nevertheless, he notes that the museum-like setting seemed to neutralize the pieces, while leaving out their main aspect, “ the process of creating itself”.

As a consequence of this, in CiP Waśko decided to “emphasise the process that was so much a part of art in the 1970’s”. In working on the list of artists, Waśko related to recent international experiments approaching the exhibition space in a performative way, such as the 1977 documenta, 9 at Castelli (Leo Castelli Warehouse, 1968), and When Attitudes Become Form (Kunsthalle Bern, 1969) (Szupińska-Myers, 141-145).

Waśko’s assumption that the clean white cube was not propitious to process art led him to consider industrial buildings as a scene for his project. This way, CiP was conceived as an ongoing program that “reveals [the] characteristics of arts in the 1970s and what happens a. between subject and object; b. inside the object; c. outside the object; d. between the objects” (Artists’ Museum, 1999).

Following this principle, the exhibition started during the installation, in August 1980, and not only after the opening in October 1981. All along the inhabitation of the exhibition space, several events were organized, including “forums, performances, concerts, readings, discussions and exhibitions” involving “all art media” and relying on spontaneity, experimentation and “the development of collaborative projects between artists with diverse cultural, political and philosophical points of view” (Archives of Contemporary Thought et al., 1982).

What brought the Lodz experience close to the biennial model was primarily its ambition to make international art accessible to a local scene, an objective that was shared at the time by most biennials and art fairs. Yet, in the case of Lodz, this goal was articulated in an unprecedented artist’s initiative thanks to the particular way of inscribing the international show in the urban context. On the one hand, the 1970s process-works were consciously connected to two important experiences of collectivism in Lodz, that of the Workshop of Film Form (1970-77), a transdisciplinary group of which Waśko himself was part, attached to city Film School; and the local constructivist movement, a.r. (Real Avant-Garde), founded by Władysław Strzeminski, Katarzyna Kobro and Henryk Stażewski.

The a.r. Group, active between 1929 and 1936, was of particular influence, and was represented in the CiP committee through the presence of Henryk Stażewski. At the end of the 1920s, the group had established a collection of avant-garde art for the Lodz public museum that was constituted through generous gifts by international artists (Skalka, 2012). The CiP project managed to enhance a solidarity network similar in spirit to the a.r. historical experience but also enacted a pioneering collaboration and situation of mutual support between artists and workers from the Polish trade union Solidarność (Solidarity).

The alliance with Solidarity came up as a response to CiP’s will to consider the social value of art and how artists could participate in social life. In practical terms, Solidarity helped Waśko to find a venue for the show, an empty industrial hall and former seat of the Budren Factory. Eventually, workers from the Union contributed to the material realization of the works in the exhibition and, in the spirit of mutual support, artists participated in the general strike organized by Solidarity in October (Jach, Saciuk-Gąsowska, 75). At the end of the show, the artists donated their pieces to the Union, prompting Waśko to plan the creation of a permanent art center based on the collection, in agreement with Solidarity, who was the legal owner of the works. The plan was put to an end one day before the signing of the contract, on December 13, 1981, when the army entered the exhibition premises and Solidarity was declared illegal. The show was seized, the works were entrusted to the Lodz Art Museum, but CiP went on, once again, through the solidarity of the international artists’ network, that payed for the publication of the catalogue and made a new edition of CiP events possible in Munich, Germany, in 1985.

3. From counter-models to the institution

In his preliminary thoughts on the A-o-P Biennial, Filliou shared the hope to create “a different catalogue…than the one of Kassel documenta”. At a time when biennials represented “different negotiations between contemporary political factors; artistic partialities; and local, national and international funding sources and cultural politics,” both A-o-P Biennial and CiP succeeded to set out a counter-model based on actual exchange between artists beyond the official geopolitical assets of Cold War Europe (Ferguson, Greenberg, Nairne, 1997). Their “catalogue” was different from institutional biennials precisely because of their utopian attempt to transgress the borders separating East and West, North and South, as Beuys poignantly summarizes, with the main specific goal of “giving solidarity and claiming solidarity” (Beuys, 1978). In this respect, both A-o-P and CiP revived forms of avant-garde internationalism and independent art shows, such as the German Secessionism movement and the Sonderbund (1909-1916) and the US Armory Show, organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. All of these shows aimed at creating a platform for presenting contemporary researches that did not find a place in art institutions of the time.

In the 1980s, the context had changed and the specific claim of A-o-P and CiP did not focus any longer on the absence of institutions exhibiting contemporary art. Rather, their ethical and curatorial statement concerned mainstream exhibition modes and discourses, in the line of Institutional Critique reflections. The choice of a solidarity model made by these artists-initiated biennials mainly commented on the possibility for artists to participate in social processes, in the case of A-o-P, and to actively share contemporary conditions and working situations, in the case of CiP.

Furthermore, A-o-P and CiP’s claim echoed, in the last decade of the Cold War, the consolidation of international cultural exchanges in the agenda of the European Community. In 1985, when A-o-P was inaugurated and the second edition of CiP took place in Münich, the itinerant biennial paradigm was at work also in the European City of Culture and, by 1996, it eventually became one of the main characteristics of the Manifesta.

Thinking back at the quick absorption of A-o-P and CiP by the mainstream art scene recalls the institutionalisation of other periodical exhibitions,[1] which all i all raises the question of the possible persistence of such forms of utopia and idealism in the biennial system. A-o-P and CiP’s emphasis on collaboration, encounters between artists and processes, sporadically surfaces in the curatorial strategies of official biennials and, more often, in counter-biennials locally organized in response to major ones.[2] In times of New Institutionalism, when the limits of large-scale show are regularly brought into question, the idea of a bottom-up biennial, rooted in and supported by local art scenes and their international network, may open up the possibility for a more sustainable international exhibition model.

Federica Martini is a researcher and head of the Master Program MAPS – Art in Public Spheres at ECAV – Wallis University of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sierre (CH).

[1] This was the case of the Venice Biennale, which first institutional draft was shaped on German Secessionism (Mimita Lamberti, 1982), and of the documenta, started in 1955 by artist, architect and curator Arnold Bode. In the case of CiP, in 2003 the Lodz Biennial, supported by the city of Lodz, took over the heritage of 1980s event in order to propose an international art biennial.

[2] With regards to biennials, examples to date include the Emergency Biennale, curated by Evelyne Jouanno, that responded to 2005 1st Moscow Biennial and invited international artists to donate a work and its duplicate for an exhibition that travelled to Grozny, in the Chechen Republic, and was simultaneously visible in Paris, at the Palais de Tokyo http://emergency-biennale.org/project.htm; the unrealized Manifesta 6 in Cyprus, meant to organize a temporary art school for the duration of the exhibition; the Do ARK Underground Biennale in Konjic, Bosnia and Herzegovina, aiming, through the subsequent editions, to create a cultural centre and collection of contemporary art in former atomic-shelters www.bijenale.ba

Bibliography

Archives of Contemporary Thought and Solidarność. 1982. Konstrukcja w procesie (Construction in process: Oct. 26-Nov. 15, 1981, 37 PKWN Street, Lodz, Poland). Rindge, N.Y.: Thousand Secretaries Press.

Artists’ Museum archive, 1999, http://www.wschodnia.pl/Konstrukcja.

Becker, Carol. 2002. Surpassing the Spectacle: Global Transformations and the Changing Politics of Art. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Beuys, Joseph. 1978. “Appeal for An Alternative”. Eng. Tr. by Centerfold Magazine, Toronto, August/September 1979.

Bishop, Claire and Marta Dziewańska, eds. 2011. Political Upheaval and Artistic Change 1968-1989. Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art Warsaw.

“Collective Curating”. Manifesta Journal, No. 8, 201.

Construction in Process, http://artistorganizedart.org/ryszardwasko

Ferguson, Bruce W, Reesa Greenberg and Sandy Nairne. 1997. “Mapping International

Exhibitions.” Art & Design, No. 52.

Filipovic, Elena, Solveig Ostebo & Marieke Van Hal, eds. The Biennial Reader, Ostfildern: Hatje

Cantz.

Filipovic , Elena & Barbara Vanderlinden, eds. 2006. The Manifesta Decade: Debates on

Contemporary Art Exhibitions and Biennials in Post-Wall Europe. Cambridge, Ma.: MIT Press.

Filliou, Robert. 1984. The Eternal Network Presents: Robert Filliou. Hannover: Sprengel

Museum.

Filliou, Robert. 1985. Invitation for the Art-of-Peace Biennial. In Wijers, 1996.

Glasmeier, michael, ed. 2005. 50 Jahre/Years Documenta 1955-2005: Archive in Motion.

Göttingen: Steidl.

Jach, Aleksandra and Anna Saciuk-Gąsowksa, eds. 2012. Construction in Process 1981 – The

community that came?. Lodz: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi.

Lyon, Christopher & Lilly Wei. 2005. “The Persistence of History”. Art in America, Vol. 93, No. 4.

Martini, Federica & Vittoria Martini. 2011. Just Another Exhibition: Stories and Politics of

Biennials, Milan: Postmediabooks.

Martini, Federica. 2013. “Pavilions: Architecture at the Venice Biennale”. In Ireland, Robert & Federica Martini, eds. 2013. Pavilions / Art in Architecture. Bruxelles - Sierre: La Muette/ECAV.

Mimita Lamberti, Maria. 1982. “1870-1915. I mutamenti del mercato e le ricerche degli

artisti.” In Storia dell’arte italiana, 5-174. Torino: Einaudi.

O’Neill, Paul. 2012. The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s). Cambridge, Ma.: MIT

Press.

Pascali, Pino. 1968. “Io la contestazione la vedo così”. Bit, No. 3, July, Milan.

Robecchi, Michele. “Lost in Translation: The 34th Venice Biennale”. Manifesta Journal, No. 2,

2003-2004.

Sholette, Gregory and Blake Stimson, eds. Collectivism after Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Jach, Aleksandra and Anna Saciuk-Gąsowksa. 2012. “Thirty Year Later”. In Jach, Aleksandra and

Anna Saciuk-Gąsowksa, eds., 2012.

Szupińska-Myers, Johanna. 2012. “From Kunsthalle to Factory”. In Jach, Aleksandra and Anna

Saciuk-Gąsowksa, eds., 2012.

Skalka, Agnieska, ed. 2012. Art Not Long Past: Collection in Museum. Lodz: Muzeum Sztuki

w Łodzi.

Thompson, Chris. 2011. Felt, Fluxus, Jospeh Beuys and the Dalai Lama. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

Wijers, Louwrien. 1996. Writing as Sculpture, 1978-1987. London: Academy Editions.