October 22, 2016

Editorial: Forms of resilience

In a way similar to several other temporarily forgotten, undiscovered or (as yet defined as) peripheral – scenes around the world, Argentina suddenly became a hotspot of contemporary art in the period that followed the severe economic and social crisis in 2001. After this moment a large number of self-managed artistic initiatives were born, that also attracted the attention of a large number of globally oriented curators. Today, as Syd Krochmalny describes in his article "The fire and its embers" in this and the next issue of Seismopolite, many of these initiatives live on:

[…] the tradition of collaborative artistic activity endures, but with different coordinates reflecting an economy that has doubled in size and a more democratic society in which the contours of social conflict have changed. […] Previously, group initiatives were primarily a means to an end. In the current context however, they may be seen as an end in themselves and as such, as shaping a singular poetics.

In a second article from Argentina, that will also continue into issue 17 with its second part, George Kafka demonstrates how the twentieth century history of Buenos Aires can be read through its public spaces, and takes us on an extensive and richly illustrated tour through the street art of the capital:

Starting in La Boca, ‘El Caminito’, an open air museum, portrays the streets that Italian immigrants inhabited with the wave of immigration in the early decades of the century. A short bus ride up to Avenida 9 de Julio will bring you face to face with Evita’s affectionate smile, gleaming from the very building where she addressed the ‘descamisados’ […].

Adam Przywara in turn shares his perspectives on what he terms an “ecology of resilience”; referring to another form of collective action and co-operation: namely the one that followed the bomb raids over Britain during World War II. Here, according to Przywara, processes of co-operation “emerged as manifold and complex […], contradicting the unified historical image of the war effort”. He thus refers to the originality in “individual gestures of resilience” which deviated from the propaganda and norms imposed on the population by the government. An example is Mr. Hayes, caretaker at Westminster Cathedral, who, after a bomb left a crater in the courtyard outside the Cathedral, decided to plant a garden and vegetables around it.

The garden constitutes the sphere of tending within a reality which emanates from the destructive power of terror. The garden on its own becomes the collective action of resilience, both providing nutrition and vitamins for the family, and aiding the immense need for psychological recovery after surviving months of air raids.

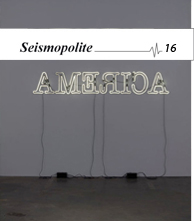

In a very different context, Lorena Morales Aparicio demonstrates the resilient art practices of artist Glen Ligon and how he problematizes relational aesthetics – particularly through his retrospective at the Whitney Museum in 2011:

By titling the Whitney retrospective “Glen Ligon: America,” the artist confirms the interpolation of national identity at the individual, singular level. Ligon confirms the interpolation of the universal through the singular and how it is not congruent. He arguably creates noumenal reliquaries that speak and breath his life’s praxis, confronting and impelling an accountability of continuing racial and social structures.

For its part, another participatory artwork, When Faith moves mountains by Francis Alÿs alludes to an ancient myth through its title, and also engenders a form of understanding of utopia, according to Riika Haapalainen.

Utopia could mean the temporary repositioning of the familiar and insignificant. Familiar but insignificant were indeed the sand dunes in the “When Faith Moves Mountains” project.

The artist Simón Vega’s Tropical Space Proyectos seems to represent another such “temporary repositioning”, if not a utopia, consisting of a variety of sculptural installations and drawings inspired by the exploration of space. The work is made of discarded objects forming space capsules, rockets, and planetary rovers that hold a heavy symbolic meaning, according to Seth Roberts:

At once a criticism of the lack of technological advancement of Central America and a statement on the legacy of the Cold War in the region, Tropical Space Proyectos is a powerful reminder of both the real and symbolic divide of modernity in the contemporary world.