December 29, 2015

A Country in Transition: The Role of Art and Artists in Contemporary Myanmar

Written by Ilaria Benini and Luigi Galimberti

I am already dead, I can say this unreservedly

It wasn't me who wrote my history

Eleven out of ten people don't know me

Historians have no idea about

My history written by historians

I have no souvenir whatsoever for sale

[...]

Misspellings, missed grammar

I don't even know how to pronounce the word 'vocabulary'

They have written my history

Then they have airbrushed me from history

My history has just begun I am going to write my own history.

From "My History Is Not Mine" by Zeyar Lynn, translated by Ko Ko Thett and James Byrne[1]

The history of contemporary art in Myanmar is a history of resistance that has not yet been written. It is a private and intimate resistance, which could not explicitly come to light in public. First of all, it is a resistance against the harshness of everyday life and a lack of resources, be they money or food, needed both for the survival of the artists and their families, and for their artistic practice. In addition to this, widespread lack of opportunities and support have created further challenges for those wishing to create a free artistic environment in Myanmar.

Concerning the documentation of the country’s art history, aside from invitation cards to exhibitions, meagre brochures, or a few articles or reviews – all of which were nonetheless inevitably subjected to censorship – only one book about contemporary art has been published in Myanmar since the advent of the Dictatorship in 1962. That too was censored. Nowadays, art exhibitions still require an approval stamp, even though more and more often officials do not carry out the pre-checks of the shows, and many gallery managers treat this requirement with ever greater flexibility. Despite this gradually increasing freedom of expression in Myanmar, experienced also in the arts sector, the country however still ranks 144th of 180 nations in the 2015 Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders.

The Dictatorship Years (1962-2011): Repression and Resistance

Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, was a British colony between 1824 and 1948. It then became the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, but was afflicted by civil wars involving many of the country's ethnic groups. After 14 years of independence, in 1962, the Army General U Ne Win conducted a coup d’état. He ruled the country from 1962 until 1988, when a large popular uprising, led by the student movement, seemed to bring the military power to an end. But that turned out to be just an illusion. Another General, Than Shwe became the new ruler, and the protests which broke out both in 1999 and 2007 were once again successfully repressed by the Military Junta.

Almost half a century of dictatorship has constituted a serious obstacle to the creation and communication of the local art community. Every exhibition had to be approved by the Scrutiny Board, which reviewed every single artwork for display. For instance, the use of the colour red was prohibited. Aung Min, one of Myanmar's few art critics and a medical doctor by profession, reported from an interview with artist Aung Myint: “[Aung Myint] stated that he had become scared of colours, and scared to use them. So he turned to monochrome and executed his work in pure black and white. The "Mother and Child" paintings are what he harvested from this shift in style and colour. In making these paintings, he put Mine Kaing paper – a type of local paper – on white canvases and drew suggestive figures of a mother and a child with an uninterrupted line. One of these paintings called, 'Homage to Mothers', reaped the ASEAN Art Award in 2002. These paintings reflect on a style, or rather a technique, that Aung Myint has developed on his own without drawing any influences from established art techniques – both Eastern and Western.”[2]

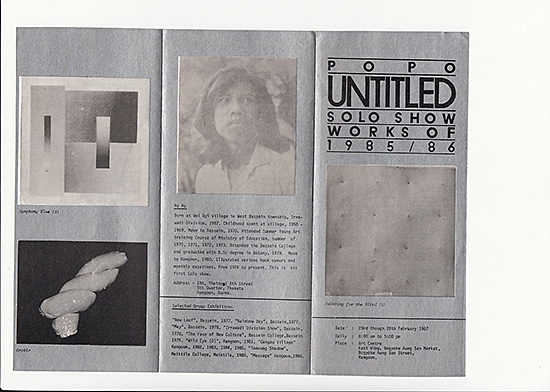

The following account by Po Po, one of Myanmar's leading artists, who has not held a show in the country for more than 20 years, despite having been exhibited internationally, goes a long way in explaining the difficulties of being (or becoming) an artist during the Dictatorship era: “In the past, around the '70s, we were living under the Generals’ government and we didn’t really know what was happening in the 'outside world'. We were living very simply and we were doing just what we wanted to do… we were looking at the previous generation, understanding what they did and what they didn’t do. We learned month by month. When I started my practice in 1977, if you had money and you wanted to buy knowledge, to buy theoretical books, you couldn't. You could buy gold as you like, but you couldn’t buy books. It was very difficult to see English books, more rare than gold. When we had the chance to encounter English books or magazines we were very happy. It meant good quality, good colours. In my early days I was interested in knowing what was going on in the outside world. I was trying to get some knowledge from old books. Everyday I was looking for old books. For example literature, what about Shakespeare, what about philosophical books, what wrote Nietzsche, Socrates etc. I couldn’t find them when I liked, maybe once a month or every two or three months. And I couldn’t find entire books, but maybe just an article explaining what Socrates said. That wasn’t satisfying for me. I can’t say that I was getting the message within the texts, but I just wanted to get information. Sometimes when you went to the grocery store, they were packing chillies for example in old English magazines. When my mother came back from the market I always checked in what kind of papers she was carrying the food.”[3]

According to Ma Thanegi, writer, translator and observer of the cultural environment, “many artists had paintings in a show refused, but not necessarily for political issues. Only a few painters were using art as a form of resistance. Among them, the best known is Sann Min.” A founder of Gangaw Village, the first collective of artists founded in 1979, and Inya Gallery – two seminal locations in supporting the development of a contemporary approach to art – Sann Min was one of the few artists who openly and continuously linked his practice to political and social criticism.

Other artists were also actively involved in political resistance. One of them was Aye Ko, who lived through the protest of August 1988 (the 8888 Uprising), which is when he started his career as an artist. He was subsequently jailed for his political activism, but eventually released three years after. In fact, prison was anything but an uncommon occurrence for Myanmar's youth. In September 1999, fearing a remake of the 8888 Uprising, the government conducted a campaign of indiscriminate, pre-emptive arrests. Among them, there was San Zaw Htway, a young political activist and member of the pro-democracy movement, which he had joined when he was 14 years old. One day in September 1999, he was arrested on political grounds and sentenced to 36 years in prison. He was released only in 2011, following a series of political reforms, which marked a slow but steady transition towards a more democratic regime.

The Political Reforms (2011-2015): A Country in Transition

San Zaw Htway spent more than 12 years in prison suffering from further limitations of freedom due to his status of political prisoner.[4] Nevertheless, as he strove to find ways to cope with solitary confinement and the miserable living conditions, he began to create his first artworks, despite not having previously received any artistic training. Because he was in prison, he did not have access to brushes, paints, canvas, or even paper. However, inspired by a story that he heard while in jail about a senior artist, Htein Lin, who himself developed his artistic practice during his jail term, San Zaw Htway started making compositions from the only colourful objects that he could find: food wrappers, cake boxes and plastic bags, items brought in from outside by other prisoners' families. Once finally out of jail, San Zaw Htway went on making his compositions with the same materials he had used in prison, consisting mainly of plastic and of all the colourful packaging that he finds in the streets of his neighbourhood. By using these materials, San Zaw Htway wants to show "how beauty can originate from rubbish", as he says.

An exemplary case of the opening-up of the country is that of Beyond Pressure, a performance art festival founded by artists and activists Moe Satt, Phone Myint and Maung Day. The festival made possible the encounter of international and local artists. As soon as the political and artistic experiences of this festival went public in 2012 however, the participating artists were arrested or deported. Yet, if the government made of "Generals in plain clothes", as it was known, would not change its nature, neither would Moe Satt and his colleagues. In 2014 the artists asked for, and eventually obtained, permission to have public art installations, artist talks and performances in the People’s Park, right in front of the Shwedagon Pagoda, the symbol of the city of Yangon. The years of military rule have nonetheless left a legacy difficult to shift, as Yangon-based researcher and curator Nathalie Johnston wrote: "The censorship board has remained active in Myanmar for several decades. Artists in Myanmar never know whether their actions might be misconstrued as against the State and therefore they do not feel truly free to express their thoughts. Just as Buddhism acts as a penetrative force within daily life, so too does politics, only having the opposite effect. Politics presents denial, dissent, duplicity and distrust."[5]

Unsurprisingly, one of the main issues faced by artists has been the circulation of information. This is due to the legacy of censorship, which carries behavioural patterns such as being secretive, as well as issues with poor communication tools, such as slow and expensive access to the Internet. Sharing experiences and information is still a challenge: few art spaces exist and, according to law, it is still compulsory to inform the censorship board about public events. Without a shared knowledge of what is happening and what is possible today, and without places and tools to collect past materials and write the history of Myanmar art, it takes a long time to activate creative artistic processes with a critical approach.

A response to the current needs and possibilities has been the establishment of the Myanmar Art Resource Center and Archive (MARCA) in 2013. Started by researcher Nathalie Johnston, and artists Zoncy and Khin Zaw Latt, MARCA is a digital and physical resource centre, partnering with local and international organizations on a range of activities revolving around art education. Thanks to a successful crowd-funding campaign, the centre is about to publish the English translation of Myanmar Contemporary Art I, a seminal book with essays, images and interviews, originally written in Burmese, covering contemporary art in Myanmar from 1960-1990, and published in 2009 by theart.com[6]. In this new edition of the book, the reader will find some of those missing pieces, erased from the first Burmese version by the censorship board. Furthermore, many artists were not included, or given pseudonyms, in order to avoid suspicion. Local initiatives such as MARCA, with an international aspiration, give resonance to Myanmar’s contemporary art scene and foster the development of art spaces and networks of art professionals within the country.

The General Election of 2015: New Hopes, Old Fears

The reforms of 2011 culminated in the general elections of 8 November 2015, the first free elections held in Myanmar since 1990. The Party led by Aung San Suu Kyi, the National League for Democracy (NLD), won the majority of seats. Although Aung San Suu Kyi is still prevented from becoming President because she was married to a non-Burmese person – a constitutional provision that was promoted by the Military Junta in 2008 – she will anyway act as the chairperson of the leading party. However, the new course of Myanmar politics will be anything but a clear path. Aside from the risk of a resurgence of military power, also the NLD and its leaders are problematic. For instance, their position on the rights of the many ethnic minorities that form the country's population, such as the Rohingyas, is controversial. Moreover, there has been surprise and suspicion regarding the fact that Than Shwe, the former military leader who had kept Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest, met with her and told her he will support her.

Not surprisingly, these political ambiguities and complexities are reflected in the practice of some artists, whose political role is far from being exhausted. To this respect, Kachin artist Ko Z says: "There has not been a big change since 2011-12, but censorship is not strong as before. We had a big hope on the 2015 election, but the country still needs to make big negotiations with the army and we still have doubt on how the power is shared for the country's future. As a member of an ethnic minority in Myanmar, I can say that most of the ethnic people are worried of the bamarization of culture and art[7]. There is still a need for freedom of expression for ethnic minorities. All of us grew up with the Junta's ideology and also we have been threatened mentally and physically during most of our lifetime, past and present. Even today, artists might get in trouble, when touching a political issue or using pictures of Junta leaders in artworks or similar."[8]

Although on a more positive note, also San Zaw Htway's account betrays uncertainty: "Since my release in 2012, many things have changed with artists. Firstly, I saw many artist groups. But they were doing everything in suspicion. 'What time we will get arrested', this is something they thought every time. Now they do willingly politics with their artistic activities. Moreover, now they do mostly support to change our country. It is occurring in every kind of art. They trust each other now; I can see this with my eyes. Nevertheless, I still don't believe the military government. The two election results 1990 and 2015 show clearly what is our people's desire. If the November 2015 elections result can not make a real difference for the future of our country, I will continue to fight against the degenerate government."[9]

Writing about the history of artistic production in Myanmar in pre- and post-Dictatorship times is a perilous task. "They have written my history" denounced Zeyar Lynn in the final verses of the poem at the beginning of this text. Facing an accusation that they cannot escape, the authors of this text have anyway attempted to give space to several voices from Myanmar's artistic present that can hopefully filter through a series of interviews' extracts, which have been left unedited whenever possible. Needless to say, this is just an arbitrary selection of experiences and reflections taken from the country's rich and plural artistic and cultural environment, which, despite having suffered from decades of harsh censorship and political repression, want to speak to those who wish to listen to them. After all, as Zeyar Lynn wrote: "My history has just begun / I am going to write my own history".

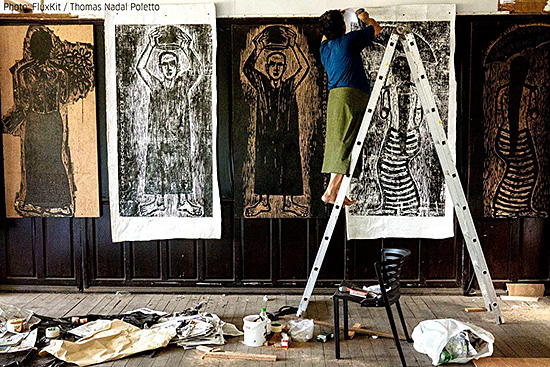

Ilaria Benini is co-founder of Flux Kit | Connecting Cultures (www.fluxkit.org) and organiser of Contemporary Dialogues Yangon, an international festival of culture and arts that took place in Yangon (Myanmar) in 2014. She is a member of the Southeast Asia Advisory Committee of the Ministry of Culture of Taiwan. She is curating a collection of books about/from Asia for add editore (Italy) and managing events at libreria Bodoni/Spazio B, a bookshop and cultural venue with a focus on Asia located in Turin. Her research interests lie with communication and artistic performances, in particular in how in the global context communication and art operate and influence social structure, distribution of power, and the daily life of contemporary human beings.

Luigi Galimberti is coordinator of Transnational Dialogues (www.transnationaldialogues.eu), an exchange and research programme for artists, architects, designers and cultural managers across Brazil, China and Europe. In the night of 31 December 2012, he joined a crowd of young Burmese partying for the New Year in a field in view of the Shwedagon Pagoda, in what was the first authorized public gathering since the advent of the military rule. In 2014, together with Ilaria Benini, he curated the donation by the publishing house Charta, Milan, of the "101 Library" to the Myanmar Art Resource Center and Archive (MARCA) in Yangon. He regularly writes on artistic and cultural production, including Myanmar's.

[1] In Bones Will Crow. 15 Contemporary Burmese Poets, Edited and translated by ko ko thett and James Byrne, Arc Publications, Todmorden, UK 2012.

[2] Interview with Aung Myint by Aung Min; original in Burmese, translation by Maung Day; published in Myanmar Contemporary Art I, theart.com, 2009.

[3] Unpublished interview with Po Po by Ilaria Benini, 3 January 2015, Yangon; original in English.

[4] This and the following information about the artist were researched for the writing of "Artist Profile: San Zaw Htway" by Luigi Galimberti, in Kolaj Magazine, Issue 6, Montreal 2013. San Zaw Htway subsequently won the Artraker Award 2014, dedicated to artists engaging and responding to violent conflict and situations of violence.

[5] "Intuitive Acts: The Evolution of Myanmar Contemporary Performance Art" by Nathalie Johnston, Final Dissertation of the Master’s Degree in Contemporary Art, Sotheby’s Institute of Art and University of Manchester, 2010.

[6] See the Kickstarter campaign "MYANMAR ART in TRANSLATION: Perspectives Post-Censorship", source: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1729607280/myanmar-art-in-translation-perspectives-post-censo/description, retrieved in December 2015.

[7] Bamar are the dominant ethnic group in the country, which also Aung San Suu Kyi belongs to.

[8] Interview with Ko Z, by Luigi Galimberti, 7 December 2015; original in English.

[9] Interview with San Zaw Htway, by Luigi Galimberti, 6 December 2015; original in English.