July 6, 2014

Editorial

Accross their various angles and points of departure, the articles in this issue of Seismopolite deal with freedom of expression and the question of how diffent artistic forms and strategies can be used to advance freedom of expression and confront censorship.

In an interview with Wanda Raimundi Ortiz and Ivan Monforte, Rocío Aranda-Alvarado gives us an insight into the work of two Latin American artists based in the US, who both address questions related to gender, race and class, and who have both had their exhibitions censored due to the explicit way in which they address these questions. In some cases, they have encountered appeals for censorship of their works from unexpected places, including the communities from which they originate. In this interview, latino artists' problem of finding a place within the metanarratives of art history and within contemporary practice as embraced by mainstream institutions, is also discussed.

Whereas Maria Spanoudaki in another article departs from a larger art-fair, Art Athina, to question forms and causes of censorship in Greece that sharply contrast with the country's status as a liberal democracy, William Aitchison, an English performance artist who has himself been active in China, sheds an inter-cultural light on the freedom of expression. He describes how imaginative ways of mixing conspiracy theory and superstition are frequently found in the Chinese public sphere (and not least on the internet) as a type of tale which includes political criticism without being censored. As a fundamental paradox, Aitchison notes that unacceptable restrictions to the freedom of speech also can be a source of creative and critical art practices which turn out to be more influential than art in most cases can be in European countries, where the full freedom of expression is acknowledged as a legal right, but where public opinion is still heavily shaped by PR and large budgets.

Freedom of expression is also a question of history writing and the possibility to see and formulate unknown or disregarded narratives which do not necessarily fit into the official or hegemonic image of reality. This is the theme of Carmen Victor's article about the Irish photographer Richard Mosse, whose landscape photography, in which he makes use of infra-red (Aerochrome-) stock, indirectly evokes the centuries-long backdrop of colonialism and "systemic violence" which forms the basis of the more recent conflicts in DR Congo. As such, among other things, Mosse's photographs constitute a corrective to the usual comments on the conflicts in the media and among western politicians, in which it is predominantly presented as a product of the last decades' tribal conflicts, genocide and humanitarian crisis, and an endemic issue.

Hegemonic media images and politically motivated descriptions of reality can in themselves, in addition to reinforcing enmity, contribute to suppressing, blurring or explaining away the causes for conflicts, and thus also contribute to maintaining and prolonging conflicts. In this context art could end up with a central role to play as a long sought space for a larger multitude of perspectives – for nuances, afterthought and reflection – but not least also as a source of dialogue. In an article from the Darfur province in Sudan, for example, Emmanuel Ebere Uzoli writes about theatre's potential for stimulating peace. Uzoli takes a look at how spontaneously established amateur theatre troupes travel from village to village to stage disagreements and hostilities that arise on a local level based on stereotypes of war. Their aim is to restore dialogue about the real causes of conflict, and to regain mutual understanding on a grassroot level. According to Uzoli this use of theatre is a method of high potential across the entire African continent.

Looking back at the relationship between photography and propaganda in Yugoslavia after World War II, Milanka Todic discusses how photography and art in general more or less subtly became objects of censorship, but also streamlined to visually promote totalitarian ideology.

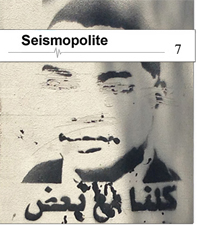

As in the former Yugoslavia, most cases of political battle are also a battle over visual representation. In recent times, the birdseye image of Tahrir Square has become the largest icon of public protest and fight for freedom. In her article Eye-snipers. The iconoclastic practice of Tahrir, Mikala Hyldig Dal defines the continuous battle over the ownership of the Square and its symbolic value as a series of iconoclasms – gestures of and counter-gestures against censorship. According to Dal, today's image of Tahrir can more than anything else be described as a pure iconoclastic gesture; emptied of real political meaning as long as the site countinues to exclude free expression and democratic political action.