May 15, 2013

For Zsi Chimera 1978-2013

How To Conjugate?

Apoptosis of Identity, Orphaned Tongues and

Drexciyan Moves in African Diasporic Narrative Futures

"I came from a dream, that the black people dreamed long ago, a presence sent by the ancestors.

I come to you as the myth, because that's what black people are.... myths"[1]

Written by Nathalie Mba Bikoro

The following is an imaginative proposition on re-conjugating self-appropriations of forms-ideas between tradition and modernity, and on how discourses of identity representation could be dismantled by considering contemporary arts practice and research as an échelle for creative and philosophical debate. Taking contemporary African arts practice as my point of departure, I suggest the mythology of Drexciya as a tunnel for research to understand ways of deciphering philosophical concepts of self, encounter, nation and transformation. By re-evaluating Drexciya as a means to deconstruct narratives about the future and their influences on socio-political and community spaces across geo-scapes, the hope is to enable a return to the future.

In the summer of 2009 during the elections, the Gabonese military shot young peaceful demonstrators, most of them children. The elections signaled perhaps the hope for the first political change after 40 years of Gabon’s autocratic presidential bureaucracy, now continuing. The controlling party PDG (Gabonese Democratic Party) had taken over the leading national phone networks Zain as well as TV channels and transmissions, paralyzed the right of free press and certain online copyrights networks which could be used to mobilize the population (only six percent of the population have access to internet), ensuring that no information could travel out of the country. As a result, people were prevented from organizing and creating networks for democratic voices. They became afraid to talk to each other and to speak their minds, and whole communities disintegrated from town to town, from village to village. Forty years on and democracy continues to be fuelled by capitalism, autocratic bureaucracy and the colonial direction which the American television network CNN has called a dictatorship. My students, friends and family were shot dead over this summer. There were over 170 deaths in Port-Gentil alone, none were named. All were children, fathers and mothers. I lost my cousin. I started to wonder what those children and young minds were hoping for, what were they fighting for? What was the authority’s necessity to massacre in the name of which leader? Or which politics? Under which agreement? Forty years on and we are further away from democratic independence than we have ever been. The youth had started to dream, their eyes started to burn. They were dreaming of a better future, they dreamed because they believed in change. Lost ideologies and hopes from grandparents and ghosts from pan-africanism came back to pose them questions. Why does one of the richest countries in the continent regress to a primitive, neo-feudal ‘democracy’ that lacks political strengths and human right laws? Why is a population of less than one and a half million subjected to the poorest standards of living and human rights since independence in 1960? This home is a zone of non-visible conflict. For most it is a war that separates thinkings, communities, networks, the physical bodies, that actively erases and renounces our histories. We became ‘separated’ ethnically, socially and philosophically, isolating us and devoiding us of experience and dialogue. Having no access to our own histories through public institutions and education, our present and future defaced of our bodies and memory through political dislocations pioneered in collaboration between Gabonese and French political parties.

A travelling body politic

During those elections, I devised an experiment called the Squat Museum. It was a travelling socio-geopolitical transitional gallery space that went from neighborhood to neighborhood in Libreville and Bitam and village to village across the river in Omboué (with an old car and trailer and using a floating boat pirogue gallery) with a selection of critical creative interactive programmes generated for people as a way to develop zones of performativity that would lead to group activities amongst communities, as a way to self-sustainability in their environments. It was a space for creation, dialogue and converging forms and ideas. These were constructed through a series of contemporary performances, dialogues, sculptural re-enactments, re-interpreting the role of myth- and story-telling (Griot-ism) in quotidian life and song, the relations between people and foods in drawing, in games, video and photography. We travelled in a small van as a hub of creative experimentation – a gallery space that became a refuge for creative and critical thinking of everyday life, and how this could be transformed and transmitted as art.

What is the use of art in isolated environments without water, electricity, clean sewage systems, safe road infrastructures and open voices? Most participants who got involved were young people and women. It enabled them to empower themselves with creative tools for communication, taking confidence in their imaginations, and to think of alternative ways of seeing their own future; their present. This creative interrogation clarified how people dealt with their personal traumas and how they generated their own therapies for themselves and each other in a series of workshops. Community organizing thus provided democratic spaces for debating and negotiating meaning. These collective social actions also allowed a re-articulation of history through which hegemonic mythical configurations became demystified. The muteness with which the disempowering of lower classes had been met, made one realize the need to democratize history by making participation a travelling body politic: The body was on trial.

Becoming another

In 2011, this journey continued with a project titled Folds in Belo Horizonte´s favelas in Brazil as part of the Perpendicular programme Casa e Rua[2] curated by Wagner Rossi Campos. The project intended to break stereotypes and tensions between the richer and poorer communities who have remained divided, resulting in the launch for a space of creative encounter that would bring both communities to work together towards a common goal without fear of prejudices against each other. Over several days people from all sides came together in dialogue and created paper boats, some with dreams written in them about what they have come to do, what they have learned and what they hope for. At night, these paper boats were put into the lake with candles in them and created a lake of fire reflecting all the stars from above, the lights from the favela and the city. They all had one common dream; to become someone else to better their homes, to become an other.

This is my first point of reference, becoming another. Exiting the Enlightenment, diving into the Negative Dialectic for reconfiguring identity and the meaning of Nation. If change, becoming another, means that we must exit, we also have to reconfigure memory: this another can neither be fixed to the past, the present nor the future, it belongs in all times at once, and is synthesized. To discuss what memory really is we also need to look at the role of the image and the device of mythologizations as substituting itself for reality; and which, according to Horkheimer and Baudrillard, have eclipsed it. The disjunctures, difference and fusion between the imaginary, the symbolic and real have played a major part in our experience of life and mutated form of modern democracy. Meanwhile, what Achille Mbembe would explain as the occupation of our imaginations as a basis for the modality of semiocapitalism, has long been signaled as a pervasive set of systematic, transgressive logic of the real and the virtual, that has imploded into an apartheid of representation and economies.[3]

Afrofuturist invasions

In a burst of Afrofuturist invasion, dislocating existing fixed appropriations of identity and nation, Goddy Leye´s The Voice On The Moon (2005) reveals a man alighting on the moon. Neil Armstrong is frozen captured in the camera. In a stream of dance steps to the sound of Cameroonian music, the man (Goddy Leye) saunters towards the American astronaut and slowly merges with him, becoming one with his body in a short burst of Afrofuturist invasion. The transformation of one to the other in a rainbow of neighbor televised images of symbols with new flags, handshakes and dance steps from Earth already breaks the division of Hegelian slave-master narratives and considers the Fanon-ian philosophy of “violence” as creative organization and dialogue for self transformation. It also re-grammatizes the discourse of history and the position of nations since the years of African independence. Leye concludes that the practice of independence and freedom is a practice of creative transformation, a narration that speaks in the past, present and the future simultaneously. Every dancer, every narrator must be a time-traveler and recognize humanity as a whole to strengthen the values needed to build a nation.

Our image of ourselves has evolved through the language and mirror of the Other in its historical modalities of global (slave) trade (including language and art forms through hierarchies of monarchy powers), performance, anthropological encounters, photography, media and politics. At the end of 2011, the Quai Branly in Paris launched an exhibition called “L´invention du Sauvage” exploring two centuries of modern exoticism, cultural apartheids, transgression in representations of human bodies as art and human slavery. Foreigners from different countries became both subjects and objects of exoticism and Western modernity, taking part in a catalytic role for the performance of ‘Other’ and a mimesis of power.

Exposing fictions of race and progress, hybridity unsettles collective and corporeal memory. In writing of his traumatic encounter with European racism in Black Skin White Masks, an analysis of cultural dispossession and racism, Frantz Fanon feels his corporeal self torn apart, to which broken fragments must be re-assembled by another alienated self. He experiences dislocation, shame, guilt and nausea. We understand through his personal analytic how cultural dispossession in histories (of colonialism and slavery) brings destructive mutilations of communal identities and social structures. Belonging to heritage is violently interrupted through depriving the past and the imagination of possibilities of existence. By comparison, it becomes evident that the exhibition in Quai Branly failed to open a discussion of contemporary modern slavery, as well as the way that we have tackled these issues and how ethnic groups (is ethnicity of any use today in a creolized world where nationhood is based on economical bias?) transform and deal with governmental laws and being in between cultures and spaces. The Quai Branly never mentions the state of the current (mis)union of the EU in challenged economical times and how these influence migrations and human rights laws around the world.

Kapwani Kiwanga, Bon Voyage (2004)

Kapwani Kiwanga´s film Bon Voyage (2004), a portrait of an African woman in her workplace, a toilet in Montparnasse Paris train station, in essence reflects much of France´s, and to a larger extent Europe’s attitude to the other, confined in no space or time of their own, frozen without permit of a better present nor future, heritage erased, language muted. The work redefines modern savagery or slavery in the treatment of foreigners. The portrait of the old early century ‘savage’ that the Quai Branly puts to light, fails to acknowledge such realities, because it is mainly preoccupied with our modern systems of representations where people fit into categories and boxes for others to measure in statistical grid systems and stare. The woman in the film is withdrawed, muted in speech and biologically removed, what Agamben calls the ‘inhuman’[4]. Losing the power of self-narration and being unable to communicate, shatters the body out of its corporeality. It is orphaned, losing its tongue, unable to create a memory without interrelations with the viewer and others. One could say that the body “returns from the future”[5] because it could not incorporate itself into experience. The repetition of the past is no longer accessible. Without access to time and space, the body can no longer perform or conjugate. Elaine Scarry investigates this ‘unmaking’ of the world as the “self disintegrating, robbed of its source and its object”[6]. As a cure the remnants of memory must ground an archive.

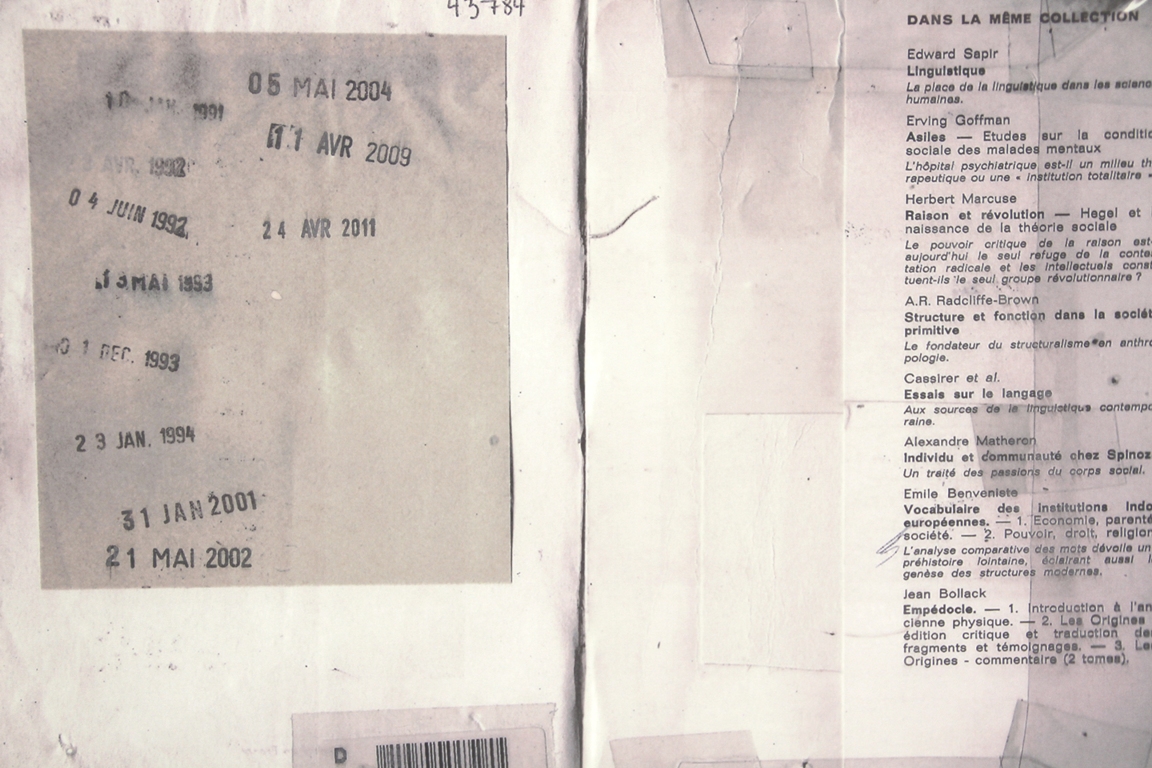

Between 1994 to 1999, Algiers witnessed a transformation in its history when the Islamic Salvation Front and Armed Islamic Group incited an aggressive Islamist regime. Oussama Tabti was six years old. 24 years later he speaks of this childhood through his art practice. I met him at the Dak’Art Biennale in Senegal in 2012 where we both exhibited together. His installation Stand By showed scanned images of the back pages of books including the date that these were borrowed from the library of the French Cultural Centre.

An interruption of dates between 1994 and 1999 corresponded to the time when the centre was closed during the regime. The censorship of literature, art and education is a testimony of a painful period and its effects on the artistic and cultural life. Tabti’s installation investigates this lost memory of the traumas of 1994 to 1999 by assembling its void. He makes the ‘robbing’ of memory a marker for an archive. “A date is a closing but for others a beginning”[7]. The silence precisely marked his history. It marks a new library that even if torn or burned down, its ashes create new voices and new choices. In such erasures and submergences, new creations of the self emerged and evolved.

African critique of consciousness and creative apoptosis

Hegelian consciousness was reformed in pan-africanism with Nkrumah and Césaire to pursue identity to the origin, to the truth of history, to what ‘rightly belongs to us Africans’, to incite a common freedom of consciousness. For Frantz Fanon, the concept of race offers no escape, and he sees it as an invented concept designed to negate equality, that must be deconstructed: “The force that shatters the appearance of identity is the force of thinking”.[8] In this procedure, he escapes Hegelian dialectics of master and slave, exiting representation to merge what Adorno in Negative Dialectics calls a “togetherness of diversity”.[9] More precisely, Fanon’s approach is similar to the way Adorno, in the chapters “Logic of Disintegration” and “Dialectics of Identity,” exorcises identity in order to break it as a totality and transform it as multiple form free to reconfigure and to cameleon-ise. Adorno wanted to get rid of Hegelian telos and its motion of identity that rejected the possibility for ‘difference’, ‘air’ or appearance (stated by Luce Irigaray as the other[10]). Against this “reduction of human labour to the abstract universal concept of average working hours”[11] which he thought imposed an obligation to become identical or total, he abolished the totality of identity with nonidentity, proposing instead ´air´ as untruth (the negative). Like Fanon’s, Adorno’s critique was thus directed against consciousness itself, in order to liberate it, allowing the “subjective pre-formation of the phenomenon moving in front of the non-identical, in front of the individuum ineffabile”[12].

In Fanon’s dialectic of the subhuman (Agamben’s “inhuman”), the “violence” that becomes the tool of social reconstruction through deconstruction of racial concepts is not an annihilation of the other (colonizer), but instead a reappropriation and incorporation of the colonizer’s violence: “It is only when the colonized appropriates the violence of the colonizer and puts forth his own concrete counter-violence that he re-enters the realm of history and human historical becoming”[13]. More precisely, this means to self-cannibalize: it is a liberation through creative apoptosis. In this sense, violence attains self-creation by conjugating the self, the performed body. In the words of Jean Paul Satre, “violence is neither sound and fury, nor the resurrection of savage instincts, nor even the effect of resentment: it is man recreating himself”[14]. But who, precisely, is leading, and who is speaking at this instance? It becomes clear that conjugating the present self requires an archive of action: memory reveals itself as a paradox[15].

Art for revolutionary times

In the rise of the Egyptian revolution and the Arab citizen’s democratic uprising, the unfolding events build new arenas of creativity and public life in the visual arts. However, two years after the revolution and the people are still being brutally massacred through all forms of oppressive aggressions. A protest against the facade of a democratic election, and the continuing corruption inside governmental institutions, Bahia Shehab’s provocative street art practice and conversation partly changed her micro society. In her unfolding street narratives for Practicing Art for Revolutionary Times, presented in Berlin’s Haus Der Kunst in 2013, she interacts with the community by organizing and educating through creative use of digital media platforms and apparatuses, working towards a realization of what Fanon calls social reconstruction aimed at “understanding social truths”[16]. Beginning a story through the medium of street graffiti, her messages become part of a physical and digital conversation across communities through new forms of public interventions. She explains how her visuals and the ongoing conversations and responses transformed her work and how her messages became informed by collective work. The cyber-street dialogues allowed for overcoming fears and discourse on social justice. She used humor and sensibility for citizen reportage and critical citizenship in learning from the past and leading new heritage and archives of remembrance.

Shehab’s resistance is also the type favored by Fanon; a form of organization that institutes new forms of relationship amongst participants. It promotes a process of culture, change and investigation that develops new ideas and forms of aesthetics and body politic, allowing for new social imagination and collective metamorphosis. To supplement the Fanonian discourse, in the following, I will demonstrate how the myth of Drexciya may prove useful in grounding an understanding of social politics and the nation.

Language of the Drexciya: Dispersing the Diaspora from the depths of the Atlantic into out of space

Drexciya is a modern myth invented for the programming of a 1990´s underground US music electro group, referring to an imaginary sub-continent populated by water breathing militaristic mutants. Their ‘aquatic assault programming’ deciphered new links between history, representation, the idea of Africa, origin and cultural authenticity. They used their synthesizer as a sonic weapon (similar to a whale’s calling, that is too high for the human ear), to pulsate, emit and radiate inharmonic tones that would project a distance between the listener and the sound in its entirety, with no room for prescribed imaginary visuals and would leave one feeling shut out to their own devices of impossible re-interpretations. At times, the sounds provoke an attack on the senses. The role of mythology, in this case the ‘aquatic invasion’ is to incarnate the soldiers of an ongoing perceptual war against control systems, codifications of Other and Self, as a form to overcome racism. With sensations of vigilance in its aggressive sonic fusions, the image and sounds make the myth into a proposition. It asks a shift in individual political empowerment, it is the undoing of the idea of the West, the territorial sovereignty of the state and of the disjuncture and difference between the imaginary, the symbolic and the real.

And so the future feeds forward into the past by inventing another outcome for the Middle Passage, this sonic fiction “opens a bifurcation in time which alters the present by feeding back through its audience – you the landlocked mutant descendent of the Slave Trade”[17]. Drexciya rejects the singular specie by identifying with the alien, the Other, the foreigner. This proposes an insight into Afrodiasporic pop culture as in Sun Rae’s instructions to citizens of the Earth where he shows that becoming alien allows an extraterrestrial perspective. This ET approach generates a new cycle towards the human. Drexciya brings this extraterritorial sequel down to earth and under the water. Their sonic fiction sinks through the streets deforming reality through a systematic confusion of technology. Drexciya rebel through cryptic myth systems, changing logics and animating conceptual explosions, which multiplies our perceptions. Their obsessive continental drift reconfigures the placeless space of the net. It communicates through mystification and conceptual ‘mess age’ (Marshall McLuhan).

“During the greatest Holocaust the world has ever known, pregnant America-bound African slaves were thrown overboard by the thousands during labour for being sick and disruptive cargo. Is it possible that they could have given birth at sea to babies that never needed air? Are Drexciyans water-breathing aquatically mutated descendents of those unfortunate victims of human greed? Recent experiments have shown a premature human infant saved from certain death by breathing liquid oxygen through its underdeveloped lungs”[18].

Seven years after Bon Voyage, Kiwanga directs Afrogalactica, a future of the United States of Africa in 2058 that is recalled as a past by another future no longer belonging to Earth. Posing as an anthropologist from the future, the artist reflects on some major themes in Afrofuturism and their role in their development of the United States of Africa Space Agency. Diving into the past to retrieve archives of popular culture, she uses science fiction to make projections about the future. But which future? Civilians form new community formations in space. In her story, Imamou mother ship was lost in its galactic mission with over 200 Afronauts onboard taking away with them a library of our ancestors´civilisations. Attempts were found to salvage this ancestry through memory but only very little could be remembered of it. History was lost. In retracing these steps to memory, the artist projects an archive of imagery of popular black and afro-modern culture. Her critic defines the impossibility to create a museum of archive knowledge based on memory because it would entail a selection of how we would appropriate history. Our memory acts as a political anthropology or anthropogagy – a cannibal selection based on a given language. Her approach enables us to explore the acting out of memory in conscious recall and continuous transmission but also in the disjunctive temporality of the unconscious and the archive. This Foucaultnian "countermemory” interrupts heritage’s normalizing imperatives, imposing beginnings, middles and ends.The fetishisation of the present that ignores historical past, “a use of history that severs its connection to memory..... a transformation of history into a totally different form of time”[19], has specific political effects. Countermemory produces a negative heritage that is for Foucault itself a form of participation in the transgressive, hybrid and performative. While seeking the Brazilian modern identity in Manifesto Antropofago (1928), Oswald de Andrade unapologically wrote a manifesto of cannibalism to de-colonize and devour foreign cultural influences that could push Brazilian identity to the future[20]. It was both a dictum against the colonizer’s power and a criticism of the colonized peoples´ hunger for what is not their own. In Vanessa Ramos Velasquez’s version, Digital Anthropophagy and the Anthropophagic re-manifesto for the digital age (2010), instead, cultural cannibalism becomes a practice for the digital age where the virtual world is a new frontier and “anyone can be a colonizer”[21]. Velasquez’ self-cannibalism is a quiet revolution and a model for acculturation: Acting ‘against memory’ she eats it for renewal. Like Deleuze to eat one’s words is to negate the leading speaker, forgetting the singular author and allowing language for the multiple, for the resonance of dialogue and to include community. Making reference to Brazilian indigenous peoples, she re-introduces anthropophagy, self-cannibalism, transmuting into the digital where cultural consumption and information becomes an apoptosis. The digital ‘cannibal’ honorably eats the foreigner in order to incorporate his strength and experiences and see through his eyes the unknown. Eating the piece of the manifesto as a Eucharist, she metaphorically spits our experiences.

In Velasquez’ work, as in Fanon’s description, the body is nauseated in the transformation. Cultural cannibalism moves like the Drexciya, like a self-apoptosis, combining and separating anew, re-inventing infinite identity beyond ethnicity and nationality, consuming and creolizing visual languages re-arranging themselves. Entailing an exorcism of identity nothing is destroyed but everything is transformed, the individual must erase and consume to invent a stronger visual culture and heritage that crosses borders of political and economic performance. If the cannibal performs, he invents cultural heritage, he cameleonises into the other surfaces of visual cultures and languages and becomes stronger and more adaptable to the (digital) evolution. Having the tribal impetus to surpass their own limitations by reaching outside of the self and assimilating and acquiring the qualities of the other in a Drexciyan transaction “a body penetrates another and coexists with it”[22]. Engaging in this ritual “we perceive the world through our bodies, we are embodied subjects, involved in existence”[23].

This is also how Adorno construes the negative dialectics of identity as a thinking of other beyond its limitations by thinking not with our reason but with our senses, our bodies “dévorer l ´Espace”[24]. The Anthropophagic ritual of self-cannibalism as Drexciyan invasion for change unites us, socially, economically, and philosophically.

Event or identity has two conjugated verbs; the present tense indicating its relation to physical time (succession); and the infinitive tense indicating its relation to sense or internal time. The verb’s conjugation oscillates between the infinitive mode (tradition) and the present time (modernity). Between the two, the verb curves its conjugation to conform to its signification. The infinitive is the empty form (eternal) permitting any distinctions of time but is pulled simultaneously in two directions between past and future. The infinitive connects language to body/being, creating a dialogue, network of assemblages and communication transmitted from Being to language. “The verb is the univocity of language, in the form of an undetermined infinitive, without person, without present, without any diversity of voice. It is poetry itself ”[25]. The infinite verb expresses the event of language of the Anthropophagic (digestion): „Your history is our poetry“. The double temporality is the performative. Bhabha wrote that “the narrative of the imagined community is constructed from the incommensurable temporalities of meaning that threaten its coherence”[26]. Bhabha accounts for this disjunctive temporality through the interplay of the performative, which is a ritual “a repetitious, recursive strategy” that refuses the reproduction of bodies and disrupts “the social ordering of symbols”[27] and the ability of people to narrativize time. When the verbs are activated to signify transitions of becoming other than, sliding into the language of events “all identity disappears from the self and the world”[28], as if irreality is communicated through language. Oswalde´s bodies are surfaces and destinations, for Deleuze & Adorno they are verbs and events. They divide infinitely in past and future always alluding to the present “thus time must be grasped twice”[29], two simultaneous readings of time that offers endless possibility. Deleuze goes on to say that if we take away these fixed significations (he opposes Adorno) then identity is lost and the self becomes blur. Adorno on the other hand sees the blur, the ‘negative’, as identifying with senses that determine experience and identity itself. It is no longer signification, it is sense, sense is the event itself, that belongs to language[30].

The Brick Moon/Who Fell From The Sky is my own story re-adapted after Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and modern experiences of homeland and identity as found in Paul Césaire's works on The Return to My Native Homeland and spaces of future modernities and new founded societies as in Elverett Hale's short 1892 story The Brick Moon. In a complex construction of fractured time travel narratives across cultures, based on philosophical ideas of Gilles Deleuze's The Logic of Senses, we follow a timeless protagonist, Alice, a little girl both young and old, black and white, girl and boy. She is the child from our neighborhoods; she is a memory of our childhoods. Falling through the rabbit's hole, she leaves her mother and joins her father on a voyage suspended between tradition and modernity through imagination and reality, which will enable her to construct her identities. She is able to time-travel through ethno-scapes by metamorphosing into male and female, young and old, human and animal as symbols of our communities and representations of West African nations. She is orphaned and must root herself by choosing to search for her family without an end goal other than to love and awake. Concurrently, Bridget Baker’s Wrecking at Private Siding 661, which was exhibited at the Wapping Project Hydraulic Power Station in London in 2010, also communicated the search of self and family through time-travel. A landing basket that poses as a human transporter is Baker’s investigation of the colonial immigrant from Britain to South Africa from 1890’s to 1930’s. Her story is attached to the relic as a document written by her grandfather in 1975 where he retraces the family’s history for Baker to unfold. The letter tells of a text that is lost, invisible outside of familial narratives. She uncovers personal and colonial pasts making evident whole narratives as a cultural memory manifested as a timeless physical space.

The Drexciyan poetic turn is the movement of relation similar to a ‘creolisation’ of roots and encounters between cultures. It is a site of opposition. Particular isolated communities must emerge for social and cultural insights to realize their potential and become re-adapted to new circumstances with new multi-faceted meanings. It refuses polarized opposites by re-conjugating narrative, pushing constant transformation where ethnicity can become creative and emergent. Intensive interactions and the possibilities of transgressing boundaries of political (aggressive) dislocation permit multiple identities, multiple tongues, multiple bodies, an archive, and a history. Edouard Glissant would oppose the term ‘being’ in favor for ‘becoming’ because according to him creating new models would not necessarily lead to progression. They should lead to creative assemblages: Adorno’s reconfiguration of the infinitive and the present tense. Identity is changing into an archipelagoisation which is a factor of space and time. The Drexciya is a currency, an act, a state of encounter and exchange. In zones of exclusions and conflicts, the Drexciyan move could permit and evolve social relations as infinite fictive dialogue that is re-conjugated between past, present and future. Can the fictive change the constellation of power structures and change communities into a transnational framework? Drexciya at least allows for the invention of narrative futures as a way to reconfigure and re-conjugate time. Along with Adorno it rejects the singular identification in favor for an invasion, in this case a re-conjugation of the self and the other, to transform it into a multiple subjunctive verb rather than a noun. Instead of reality it travels to the virtual (subjunctive verb) deforming mythological systems, engineering conceptual explosions through visual culture and art forms. This engineering of the virtual subjunctive verb triggers new forms of dialogues and configurations of identity that allows for the recognition of creolized language, identities and tones of Nation building. Drexciya allows us to “move through light, through sound, through ideas, everything unfolds to the speed of light”[31].

Kempinski (2010), directed by Neil Beloufa, releases a similar process through assemblages of narratives and reconfigurations of the past, present and future tenses through the moving image. In his strategy the image becomes virtual and moveable, giving it access to a new form of nonidentity. The virtual begins its narrative of talking of the future in the present tense which shows Beloufa´s intention to go beyond the linear form and narrative of historical archive. His anonymous protagonist time-traveler describes how he moves, how he is being;

“the houses move like humans. We see buildings like stars, we only see the light, no bricks, only in light form; there are no settled doors in it. We enter where we want, we go out when we want and how we want”.

The protagonist chooses what he sees, how he travels and what he wants. It is not a case of seeing what is there, but of creating a reality that is not instated in truth but belonging to its nonidentity, its subjunctive other. Nothing is contained in its definition. The untruth of any identity and its conceptual ideas live in the cavities between what things claim to be and what they are, creating a Utopia above identity and belonging, and above contradiction that according to Adorno allows for a togetherness of diversity’.

He continues to the viewer with his wives as cattle:

“Once you only have thoughts of this thing, you are with it, men have changed.

Human beings are made for that today once you think of something you have it.

It’s not a machine it is the human being´s thought. It is the flow of your imaginations.

You can do whatever you want with it. Humanity has changed, men have evolved ”.

In this planet both Earth and no longer itself, the men that have become instinct of the old human form that we now belong to have evolved through this Drexcyian paradox or make-up. From ascending from water to Earth, on this planet the men or aliens have made the Drexcyian move from Earth to sky to the unknown. The unknown has become a home where houses are stars and people know exactly where and who they are. Showing that the African is beyond life becomes the only possible expression of freedom and dignity.

But then another alien comes to the screen; he speaks in the future tense and may not belong to the same present tense as our familiar protagonist:

“We will be firing rockets into the heavens and placing satellites in orbit; this will allow us to know much more about the other, about other planets and the beyond”.

He declares that identity is infinite, it does not belong to the future nor present tense but to the virtual subjunctive verb of a ghostly past that is coming back into the future. His future is not present, is not past, it is infinite. He announces that he is willing to change into another in infinite times just as far as that every planet, every star, his invasion for opening dialogue with the unknown will allow new forms of home where people can recognize each other and know where they are. A position well re-instated with Goddy Leye’s video for a man to open his song, open his dance, and open his skin to become the other, and remembering that the verse is about humanity. With humor, he also ‘eats’ the alien suit; he becomes a light that travels through the speed of imagination and dignity. In a way, he offers a perspective on identity and place morphed in under one century from Friday-ism (the obedient slave), to Frankenstein-ism (the departure of man to object, identity as object or Fanon-ian transition from black man to French citizen) to PeterPan-ism where the human looses or transgresses his locality of representation (looses its present-future tense) and chooses his path to identity ascending into the heavens into the unknown as a form of Drexciyan invasion to become another infinitely where reality becomes virtual. A constellation for a new galaxy, a new philosophy. We no longer identify with the object but with people and things. Similarly, Zambia’s forgotten Space Program from 1964 lead by Edward Makuka Nkoloso who organized an Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy to allow for conceptually engineered thought and forms-ideas, questions notions of representation, origin and truth. His story inspires a re-evaluation of the line between possibility and dreams, and Cristina De Middel is his acolyte in the way she conflates invention and truth. In 2010, her Afronauts retells this story in photography, as an ethnic caricature of a unique story. “The images are beautiful, but it is built on the fact that nobody believes that Africa will ever reach the moon. It hides a very subtle critique to our position towards the whole continent and our prejudices”[32]. In both bodies of work there is truth and fiction, but on opposite sides. The game works when there is a balance between the two. De Middel relaunches and searches for new forms by rehearsing evolution, in a way that deconstructs mythology of imbedded prejudiced meanings through signs and interrogates the process of history itself. By its way of re-assembling the other and deconstructing mythologies also comes to mind the film Elmina by Revel Films. This is a Ghanaian production which presents humorous ethno-scapes of West African narratives. Exhibited at London’s Tate Britain in 2010, the Ghanaian melo-drama featuring popular local actors also includes a black male farmer as the lead protagonist, played by the white, american artist Doug Fishbone, the man who tries to save his community whose land will be sold to foreign oil corporations. The important achievement of the film was questioning tenses and mythological constructs by pushing the role of the viewers who follow this story in how they perceive and bring elements of panopticon gazes and expectations on the presented contexts. We can never quite settle with the idea that Fishbone is acting a leading West African character whose proverbs against slavery and the colonizer seem to loose all its own reality and meaning in fact. At times he is white, at times he is black, at times he belongs to neither. Everything is put into question on the nature of his character and we can never trust the image that he wants to ‚protect’ his community which is not his own. It cuts the cinematic effect in two, it makes the Deleuzian fold visible. He is the chevalier of the story yet we can never quite trust him. “We are allowed one role and breaking out of it disturbs constancies, the frame within we see each other and which facilitates social discourse”[33]. These ambiguities are never explained neither answered but they do open questions about the nature of the image, the nature of representation and how audiences interact with this unusual fiction. How far can people extend the suspension of disbelief and take a narrative for its own terms? Fishbone’s presence is in fact a “doubling, dissembling image of being at least two places at once.... and it is impossible to accept the (colonizer’s) imitation of identity”[34]. Identity is never a finished product.

“The question of identification is never the affirmation of a pre-given identity – it is always a production of an ‚image’ of identity and the transformation of the subject. The demand of identification – that is, to be for an Other – entails the representation of the subject in the differentiating order of Otherness. Identification is the return of an image of identity which bears the mark of splitting in that ‘Other’ place from which it comes.... the primary moments of such a repetition of the self lie in the desire of the look and the limits of language. The uncertainty that surrounds the body certifies its existence and threatens its dismemberment ”.

Memory could be placed un-linearly beyond the tenses of past, present and future. Memory belonged to body corporeality, that could liberate the self. The body and its image can re-invent spatio-temporalities connecting migratory narratives forming new traditions belonging to past, present and future. In Wretched of the Earth Fanon states that these narratives must be for political and cultural inertia as violence. The term of violence stated here is not so plain; by violence he expresses the shifting of relations of power by the role of the Griot (storyteller) to mobilize his imagination to conjugate cultural memory with the realities of the present and exit towards new (inter)national consciousness or to what Paulo Freire stated as education and community[35]. Fanon refuses to be a “prisoner of history”[36] in favor for endlessly creating himself in the world, which to him means reconsidering signs and meanings of cultural roots The political is thus firmly embedded in aesthetics, and the artists mentioned earlier also challenge the mimetic conception of representation by intervening in codes of narration and liberating imagination. Adorno explains his dialectic of identity as an “anti-narrative that is not given through any totalizing or transcendental perspective, but emerges as a virtuality in the interstices of its different registers and in its engagement with the imagination”[37]. As such it problematizes claims to truth of the different registers of histiography and fiction of art practice. We perform to reconcile, to re-conjugate, to move in time and space, to become tradition. It is part of a process in global contemporary art which will liberate the possibilities of the archive and impact on notions of community and nation. After all, the orphaned image, the archive is a “system of relations between the said and the unsaid”[38], holding the power of interpretation. We must create mythologies like a Drexciyan ideological weaponry or self-cannibalize to obliterate the marginal.

“The statues are no longer dead in their cases. Our histories are no longer mute. The hierarchy of value is being replaced by an equality of curiosity and exchange”[39].

“The question of the archive is not [...] the question of a concept dealing with the past that might already be at our disposal or not [...], it is a question of the future itself, the question of a response, of a promise and a responsibility for tomorrow”[40].

The examples of narratives of Africa and its Diasporas re-conjugate and re-invent time. The re-invention of time and space governed by its own set of rules can provide us with a new fabric of experience allowing us to return to the everyday reality with a different mind and different clues to decipher its enriched layers of meaning. Could Drexciyan myth be offered as a solution for breaking misrepresentations and influences on diasporic narratives? Will we look at ourselves differently and change consequences? Will we resuscitate the image of our drowned fathers and mothers in the political frameworks? The future is self-cannibalized and re-conjugates its digested memory to manifest possibilities of exiting Hegelian dialectics of representation and simultaneously converging both past and present, tradition and modernity, to re-conjugate identity. The mythology of the Drexciya that accords to the socio-political interferes with the locality of self-appropriation and reconstructs communities. In thinking differently and considering the world, not only my own country, as my home, could it bring new spaces of creative liberation when small communities break their divisions through reconstructing their narratives as eating the other (oppressor) and opening new constellations to navigate from? I am not certain how graphically this will change politics of many countries and old staled set of minds that impoverish each other’s awarenesses, including Gabon, but I would hope for evolving accessibility to language and creation of new archives for a history that would enable transformation of interaction and community. That, above all, is the strongest politic. Laws have to be changed and maintained, but for the future to impact it needs imagination and that is inseparable to artistic practice. In this spirit, the Drexciya lives in the discourse and research of art practices with artists that interrogate and rupture dominant forms of geographical identities and archives of historical representations of mundane dichotomies. The works of Kiwanga and Velasquez do not assume grammar. Their visual narratives re-conjugate the socio-political spaces of identity and histiographies to reconstruct a new dialogue for local-global exchange. Their practices reveal chimeras of tradition and modernity that make present ideologies suspect. The Africa of Africa, the Africa of Latin America and North America, the Africa of Europe and the Arab World have organized great leaps. These creative local global communities, now realized as over hundreds of institutions like CCA Lagos, ANO Ghana, DNA Foundation Gabon and Kuona Trust Nairobi, which incessantly communicate and evolve with each other are building their own Brick Moons where eventually dispersed communities can embrace new possibilities of artistic practice, especially through the digital space, bring new inventions, new narratives completely equipped with the politics of the world to configure a space, that becomes an open nation for which the constellations of people and places are brought together and where everybody can begin to recognize each other. We are no longer orphaned; we are finding our ways back to an invented future, finding our mothers and fathers and so to speak develop with each other’s tongues.

1 Sun Ra, BBC Documentary: Sun Ra, Brother From Another Planet, 2005 Extracts from Space is the Place 1974

2 Mba Bikoro, Nathalie Triangle to Perpendicular: Division, Interaction, Coonnection. Why the body is a space for breaking geographical borders and creating horizons for alternative social spaces for the beginning of historical consciencism; Perpendicular Casa e Rua ed. Wagner Rossi Campos; Dados Internacionais de Catalogacao na Publicao 2012:130; ISBN-9788561659233 (English and Portuguese trans.)

3 Mbembe, Achille De La Postcolonie, Essai sur l’imagination politique dans l’Afrique contemporaine; editions Karthala publications; 2000:266; (in French); ISBN-9782845860780

4 Agamben, Giorgio Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen, New York: Zone Books, 2002;47

5 Fisher, Jean Diaspora, Trauma and the Poetics of Remembrance originally published in Exiles, Diasporas & Strangers ed. Kobena Mercer, Iniva 2008:193

6 Scarry, Elaine The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World Oxford University Press USA 1987

7 Dexin, Gu, Art of Change: New Directions from China, Hayward Gallery official website: www.china.couthbankcentre.co.uk/artists/#gu-dexin

In the same year, artist Chen Zhen’s installation was displayed at the Hayward Gallery in London. It comprised of a mound of burned books turned to ashes falling out of a giant pouch. His interest was to explore topics of multiculturalism and globalization, cross-cultural social dynamics. He acknowledges that he belonged neither to China nor the West but to somewhere in between. Repeated like in other times of history and parts of the world, the Chinese regime had influenced the destruction of literature books.

8 Kebede Messay Africa’s Quest for a Philosophy of Decolonization Editions Rodopi 2004:83

9 Adorno, Theodor W. Negative Dialectics, trans. E.B. Ashton, Routledge London & New York 1973:145

10 ibid, 1973:145

11 ibid, 1973:145

12 ibid, 1973:146

13 Seregueberhan, Tsenay The Hermeneutics of African Philosophy; New York Routledge 1994:71

14 Jean Paul Satre summarizes “violence is neither sound and fury, nor the resurrection of savage instincts, nor even the effect of resentment: it is man recreating himself

15 For Gilles Deleuze who calls this same, creative violence a cannibalized humor, the only available choice is “either to say nothing or to incorporate what is said – that is to eat one’s words”. See Deleuze, Gilles Logic of Sense trans. Mark Lester, ed. Constantin V. Boundas, Continuum New York Press 2004:153

16 Fanon, Frantz The Wretched of the Earth (1961) trans. Constance Farrington, Hammondsworth: Penguin1985:190

17 Eshun, Kodwo Drexciya: Fear of a Wet Planet originally published in The Wire magazine issue 167 January 1998

18 The sleeve notes to The Quest CD are an origin story, a prequel that links genetic mutation to recent breakthroughs in liquid oxygen technology and retroacts both back to the Slave Trade.

19 Foucault, Michel Nietzsche, Genealogy, History in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice; Selected Essays and Interviews, ed. D.F. Bouchard Ithaca Cornel University Press 1977:151

20 De Andrade, Oswalde La Cultura Cannibale: da Pau-Brasil al Manifesto Antropofago, Meltemi publishers 1999:28

21 Ramos Velasquez, Vanessa Digital Anthropology and the Anthropophagic re-manifesto for the Digital Age, live performance presentation at Transmediale 2011 source: www.quietrevolution.me

22 Deleuze, Gilles Logic of Sense trans. Mark Lester, ed. Constantin V. Boundas, Continuum New York Press 2004:8

23 Merleau-Ponty Maurice Phenomenology of Perception Routledge 2012:298

24 Deleuze, Gilles Logic of Sense trans. Mark Lester, ed. Constantin V. Boundas, Continuum New York Press 2004:78

25 ibid 2004:41

26 Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture Routledge Publishers edition 2 2004:227

27 ibid 2004:234

28 Adorno, Theodor W. Negative Dialectics, trans. E.B. Ashton, Routledge London & New York 1973:172

29 ibid 1973:172

30 ibid 1973:25

31 Kempinski, move through light, through sound, through ideas, everything unfolds to the speed of light”.

32 De Middel, Cristina, in her own words www.photobook.wordpress.com

33 O’Doherty, Brian Strolling with Zeitgeist edit of Frieze Talks 2012, published on Frieze Issue 15 vol.3 March 2013

34 Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture Routledge Publishers edition 2 2004:198

35 Freire, Paulo Educational for Critical Conscioussness Bloomsbury Academic publications 2005:32

36 Fanon, Frantz The Wretched of the Earth (1961) trans. Constance Farrington, Hammondsworth: Penguin1985:194

37 Adorno, Theodor W. Negative Dialectics, trans. E.B. Ashton, Routledge London & New York 1973:164

38 Agamben, Giorgio Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen, New York: Zone Books, 2002;145

39 Offiriatta-Ayim, Nana Speak Now, published for Frieze Issue 139 May 2011 surce: www.frieze.com

40 Derrida, Jacques, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression trans. Eric Prenowitz, Chicago & London; the University of Chicago Press 1996:36