May 15, 2012

Editorial

Reimagining the political geography of “place” and “space”.

By Paal Andreas Bøe

The distinction between “place” and “space” is fundamental not only to much art, but also to our global situation within a neoliberal political geography. The construction and exploitation of a particularism of the local seems indigenous to the logic of neoliberalism, in the sense that it relies on the opposition between place and space to be able to expand in the first place. Among other things, the space-place dichotomy facilitates the reduction of developmental issues, political unrest or violence to irrational expressions of local misguidance, backward culture or belief systems. When the evolution of neoliberal space is merged with democratic and civilizing pretentions, the otherness and fixed specificity of places appears to be a legitimate pretext to expand into always new (potentially profitable) areas in and beyond the periphery.

The self-fulfilling prophesy of neoliberal geography also constitutes an effective impasse in alternative visions of political geography – on the one hand, by making the critical reconstruction of place and its interconnectedness with a larger picture, beyond the dichotomies of space/place and local/global, superfluous – on the other, by dissimulating any locally based meaning of universality that cannot be reduced to the civilizing prospects and ideals of neoliberal universalist geography. In this sense, the self-upholding myth of the local which neoliberal geography feeds on seems to express another form of orientalism, convincingly presenting itself and its worldview as the necessary cure to global and local problems, and reversely; presenting political issues in localities beyond its borders as a temporary void in its over-arching, inescapable logic.

The Spring Issue of Seismopolite takes its cues from a high variety of cases, contexts, theoretic perspectives and artistic endeavors to discuss how neoliberal political geography – as well as the interrelationships between, and definitions of “space” and “place” – can be reimagined.

The above mentioned particularism of the local is for instance elaborated through the concept of “reserves” in Shaily Mudgal’s article on Jarawa tribes in India. In the article Mudgal demonstrates how “reserves” become orientalized and commodified as deviant, backward places for tourism (among other) purposes, and at the same time, how they reveal the legacy of colonialism, only now exercised by a government within decolonized national boundaries.

In a personal account Neery Melkonian reveals the definitional obstacles in pursuing the local affinities between Armenian-Lebanese artists in exile – displaced by a more recent experience of war and migration, and removed from a notion of their ancestral homeland – and the necessity of doing so, without succumbing to a traditional concept of “Diasporas”. According to Melkonian, the works of these artists “invite critical inquiry to better understand the messiness of contemporary experience” in which past traumas or events are present-absences, and doing so without the notion of “return” to an originary homeland, usually implied by Diasporas with a capital D.

In her essay on the The Ecopoetics of Space in Snyder, Merwin, and Sze, Jenny Morse investigates how boundaried conceptions of space limit the natural world in the works of prominent ecopoets Gary Snyder and W.S. Merwin. In a comparative reading, she demonstrates how the neglect of the central problems related to the opposition between space and place undermines poetic attempts to reconfigure human/nature relationships.

Moreover – while in a contemporary and decidedly urban, neoliberal, parisian setting Carola Moujan analyses the potential of digital furniture and mapping technologies to provide what Walter Benjamin claimed to be the condition of an authentic city – namely the experience of origins, not just its narrative – Brian Brush (in his article "Beyond Reference: Continuity, Memory and Territory in Cartographic Art") imagines alternatives to map-centered cartographic artistic practices. According to Brush many such practices unintentionally proliferate power structures which originated in the historic function of cartography in the charting of territories for political administration.

In a photographic essay Paula Roush documents the Meia Praia estate in Lagos, Portugal, where forty-one houses were built as part of the national housing programme (SAAL) after the Portuguese revolution, which proclaimed a “people’s right to place”, yet became dissolved in 1976. Many years after the ownership of the houses was granted through public deed, the legal documents have been “lost” and the site earmarked for luxury hotels and resorts. In this context, Roush asks, can the photographic image still provide a critical tool for an ‘archaeology of the recent past’?

In the conception of the Gija, history is never resolved or complete, but constantly replayed and extended. And in the paintings of Paddy Bedford, Timmy Timms, Janangoo Butcher Cherel and Rammey Ramsey – according to Henry Skerritt; “both the landscape and the canvas are reimagined as sites for the successive accumulation of meaning, memory and place; conjured into being as the meeting place for our cultural communion. They show us what it means to be contemporary, and how to comprehend a world of accelerating multiplicity.”

If time has come for us to reimagine the political geography of our times, as well as the interrelationships between, and definitions of “space” and “place” that it entails, is it thinkable that art could be an ideal site for such reimagination?

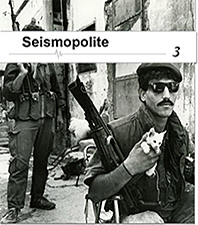

Front page: Aline Manoukian, A Palestinian fighter holds a kitten in the refugee camp of Burj Al Barajneh near Beirut. It was taken on July 8, 1988 a day after pro-Syrian Abu Mussa’s fighters ousted the PLO from the refugee camp, Arafat’s last stronghold in Beirut.