May 15, 2012

The past persists in the present in the form of a dream

(participatory architectures, archive and revolution)

By Paula Roush

In the context of Portugal (the country I was born in), a late-arrival to the eurozone and today declared one of its dysfunctional peripheral members, can the photographic image still provide a critical tool for an ‘archaeology of the recent past’? The commonalities between archaeological and investigative art practices, namely to make visible that which is oftentimes not factually constituted and forgotten, may become apparent when visualising neglected aspects of contemporary experience that disrupt and puncture dominant ideologies. For the type of contested site that is the object of this study, photography, provides a different set of lenses to scrutinise the fleeting relationship between image, memory and history.

The site that concerns me here is the Apeadeiro estate, in Meia Praia, by the waterfront surrounding Lagos city in southern Portugal. The estate was developed as part of the national housing programme code-named SAAL 'Servico de Apoio Ambulatorio Local' (or Mobile Service for Local Support), that emerged in the short but intense experience of participatory democracy during the Portuguese revolution of 1974-75. From this very experimental programme of people’s ‘right to place’ that lasted less than two years, resulted around 170 projects and more than 2500 houses in the process of being built all over the country.

The estate grew out of the collaboration between the architect José Veloso and a community of fishing families that lived in self-built huts. The families came from another southern village in the early 1950s, in search of better fishing conditions, and occupied a small enclave in the Meia Praia seashore, one of the most beautiful beaches in the Algarve coast. Portugal didn’t have a proper social housing programme at the time, so informal settlements and slums were a regular feature in the periphery of cities. That would start to change in 1974, when the Housing ministry, run by architects influenced by Marxist spatial theory, placed architectural teams in disadvantaged communities to figure out ways to improve their precarious living conditions.

When Veloso set up a SAAL operation with the Meia Praia families, filmmaker Antonio Cunha Telles joined the team and recorded that process in the film Continuar a Viver (Carry On Living, 1975). Since 1968 European militant cinema had been filming the working class struggle. With Cunha Telles, the sea takes the place of the factory and the sea workers perform for the camera as citizens engaged in an emancipatory process that involves to get organised as a housing association, and apply for state funding and ownership of the land.

They called themselves the Association 25th of April, whilst they had been known as ‘Indios da Meia Praia’ (Indios of the Meia Beach) since they migrated to the area. The term indios, as the Lagos population called them, implied both foreigner and subaltern positions. They eventually appropriated the label, made a joke of it, and shrug if off in a funny self-deprecating way. When the protest singer Zeca Afonso wrote the soundtrack for the film he called it The Indios of the Meia Praia and was the first to celebrate the bravery of that community, that had the courage to demand access to the means of production. The song has been so popular throughout the years, that it has slowly become an anthem for the revolution. So whilst in fact many people have never visited or seen the estate, the so-called Indios became a legend and regularly reappear in a new cover version in TV shows, European song contests and the yearly celebrations of the 25th April. In YouTube are currently uploaded more than twenty different cover versions of the song.

From 1975 onwards, forty-one houses have been built following a modular typology of evolutionary housing. The basic unit was the one bedroom flat, and each unit contained five additional options of interior organisation allowing the family to develop their space up to a five bedroom flat, according to their household size. The architects made the proposals, elaborated the technical aspects of the construction and all decisions were taken in collective meetings, where almost everyone participated: “It was a very cohesive, lucid and coherent group in their decisions. They didn’t want each family to be simply building their own house. Instead, everyone worked in all the houses collectively, and they would all be built at the same time.”

The operations SAAL were eventually dissolved in 1976 by a government invested in joining the neoliberal capitalist model. In a process of normalisation for the Portuguese society, hegemonic models of western-style consensual democracy have replaced the participatory experiments put in place during the revolution.

The estate reappears on screen in the film Elogio ao Meio (Tribute to the Meio, 2005) by Pedro Nunes Sena. The title contains a pun, as the Meio (the half), besides being the name of the location, also means a process that was stopped half way through. The houses face the camera, the windows are their eyes and look back at us. The residents walk in streets that have not been paved yet, in the estate that never became part of Lagos city. They had no right to the place, after all. A profound historical split is revealed: they perform in the space they built three decades before, this time as dispossessed citizens, walking through the semi-ruins of the utopian social housing project.

The feeling that the local Council has been sabotaging the maintenance of the estate is pervasive, with examples being provided where the wrong building supplies were sent in and the estate left to decay, ready for gentrification. Right now the estate is threatened with demolition and the residents susceptible to dispersion into other separate council estates. The situation became so absurd that today, many years after the ownership of the houses was granted through public deed, the legal documents have been lost and the site has been earmarked for luxury hotels and golf resorts as a part of the new waterfront touristic resort.

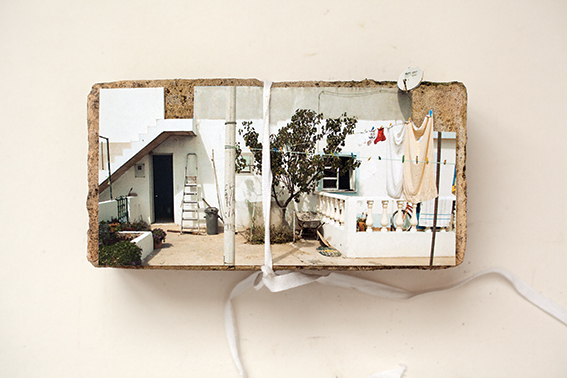

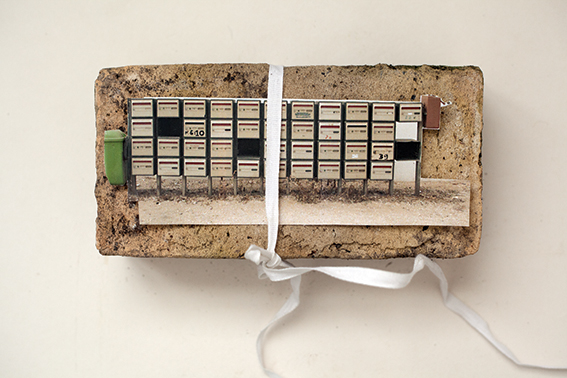

Life in the estate has been wrapped up with the codes of ethno-documentary representation and the politics of image, already since its inception. As conditions changed, so too did the iconographic status of the people which today, more than anything perhaps, provides an allegory for the country’s ambivalent relationship to the memory of its revolution years. Hence, for me, an emerging issue associated with the photographic objects of the houses is that of making visible the tension between the lived and the represented spaces. Rather than as a documentary tool, I find that photography here carries a potential to reflect how time and political rhetoric transformed an architectural utopia: How and why it became such an unruly and symptomatic site, eventually made abject and thus relegated to the margins of discourse and normativity.

When I first visited the site, I made it my task to photograph all the forty-one houses. I followed an impulse to observe what happened to a typology of architecture that was initially based on a modular repetitive pattern and today became a patchwork of modified dwellings, customised and personalised according to its inhabitants. I received initial support for academic research in the area of memory, history and space. Since then, my efforts to show the work have met obstacles that are not too dissimilar to the fate of the estate. The Centro Cultural in Lagos suspended their invitation to show the work when the council manifested their opposition to the project. Then in London another commission for the Borderline project was also withdrawn accused of becoming “too much about the houses,” and “déjà vu.”

Little by little I experienced the same resistance that the estate has encountered, and it was therefore in a state of anger that I started cutting out the houses and initiated this un-archive of brick-images, bound by the same cotton tape used for tying up bundles of documents in the Portuguese National Library. The result is a literal photographic archaeology of a dispossessed site ready to be thrown against a glass wall of political impotence. Could such twofold reappropriation of ruins represent the latent power of images?

paula roush is a Lisbon-born artist and researcher based in London.

Since 2006 she has developed the photobook programme, a publishing research project about artists' publications and photo publishing technologies, based at the London South Bank University, and she also teaches in the Art and Media Practice MA programme at the University of Westminster in London. She is founder of msdm: mobile strategies of display & mediation, http://msdm.org.uk/

1. The Portuguese financial crisis in the backdrop of the Eurozone is not strange to its own pejorative terms, with acronyms such as PIGS used to refer to the economies of Portugal, Italy, Grace, Spain, and Ireland (PIIGS)

2. Buchli, V. 2010, Archaeology of the recent past, notes on knowledge production. In Fugitive Images, ed. 2010. Estate. London: Myrdle Court Press, pp. 105-116.

3. For further details and numbers, visit the online archive Processo SAAL http://www1.ci.uc.pt/cd25a/wikka.php?wakka=projsaal [accessed March 23 2012)

4. Nunes, J. A., Serra, N. ,2003, Casas Decentes para o Povo: movimentos urbanos e emancipação em Portugal, in Boaventura de Sousa Santos (org.), Democratizar a Democracia: Os Caminhos da Democracia Participativa. Porto: Afrontamento, 213-245. Departing from Foucault’s disctinction between specific intellectuals (applying their professional expertise) and universal intellectuals (with a political vision), the authors explain SAAL’s radicality in architects refusal to separate the realms of action and political engagement, inspired namely by Henri Lefèbvre and Manuel Castell’s work.

5. Examples include: Group Medvedkine de Besançon (1969), Classe de lute, filmed by a group of factory workers and Louis Malle(1972), Humain trop humain about the Citroen factories.

6. The SAAL programme funded the housing associations directly, with a contribution of 40% (non-refundable) grant for a 60% self-raised input. Simultaneously, local councils were instructed to pass the ownership of the land to the families occupying it, thus legalising their squatting. This proved to be the most radical but also the most problematic aspect that led eventually to the interruption if not downfall of the process, specially in a touristic coastline as Lagos, due to speculative value of land.

7. Named after the day in 1974 of the military coup d’état that overthrew 50 years of fascist dictatorship; the estate is also sometimes designated as 25th April estate, in addition to the initial name of Apeadeiro estate, due to its location by the train station, one stop from Lagos city.

8. In Portuguese the term can refer both to indigenous populations or outsiders, as in colonial hegemonic speech.

9. See the YouTube playlist Os Indios da Meia Praia http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL566BC2DA7E0FBDFD including: Dulce Pontes, star of world music, in a live concert for state Television channel 1 in 1992, Vozes da Rádio performing a capela version in the program Turno da Noite" chanel 4 in the 25th April 1994. (20th anniversary of 25th April), Rui David, in a concert tribute to the Carnations Revolution in April 2007, and Flora one of the contestants in the reality TV Music Academy song contest in 2003.

10. Interview with Jose Veloso, Lagos, 2010

11. For further details, read Santos, B.S., Nunes, J.A.,2004, Introduction: Democracy, Participation and Grassroots Movements in Contemporary Portugal’, South European Society and Politics,9:2,1 — 15

12. My field trip to the Apeadeiro Estate was supported with a grant from the Centre for Media & Culture Research at the London South Bank University

13. The Borderline project (2009-10)was supported by Chelsea Programme, Chelsea College of Art & Design & Tate Britain Cross Cultural